When Rabbi Miriam Terlinchamp appeared on an episode of the “Judaism Unbound” podcast last year to talk about her new online Jewish conversion class, she didn’t know that two listeners would soon change the trajectory of her life.

Those listeners, Ari Kingsman and Joshua Phillips, were cellmates inside the Monroe Correctional Complex in Washington State with a shared interest in Judaism. After listening to her podcast, they wrote to the rabbi asking if she would help them convert.

“I just listened to your interview on ‘Judaism Unbound,’ and you said that the gates should be open for more people,” Phillips wrote to Terlinchamp. “I hope I am one of those people.”

In the year-long journey that followed, Terlinchamp would take up the challenge, traveling across the country to supervise two decidedly non-traditional conversions to Judaism from inside a prison — a setting where, to her knowledge, no other rabbi has agreed to stage a conversion before.

“If you would talk to me five years ago or 10 years ago, no way would I have done this,” Terlinchamp told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency about the experience. She had to jerry-rig so many aspects of the conversion ritual that she worried the endeavor could “strip me of my semicha” — her rabbinic ordination. But as she got to know Kingsman and Phillips, she saw that their desire to convert resonated with her own attitudes about removing what she calls the “gatekeepers” to Judaism.

“What I’ve come to understand through Ari and Josh is that, the more you question your authenticity, the more you need others to affirm who you are, the more the tradition speaks to you,” she said.

Terlinchamp chronicled the prison conversion process in a new spin-off podcast for “Judaism Unbound,” called “Tales of the Unbound.” The seven-episode series wraps this week.

For Kingsman, who is serving a 25-year sentence for murder, and Phillips, who is serving life for soliciting murder and burglary, finding a rabbi who agreed to convert them was a revelation. The two had spent years in prison studying Jewish texts on their own, joining up with a prison Jewish group and absorbing Talmudic lessons that seemed to reflect their desire for restorative justice. They came to see Judaism as central in their efforts to atone for and move past their crimes.

The journey has been professionally transformative for Terlinchamp, too: After 13 years as a congregational rabbi in Cincinnati, last summer she took a new job as executive director of Judaism Unbound, the parent organization for the podcasts and a digital project that reimagines Judaism for unaffiliated or disaffected Jews. She cited the prison experience as her chief motivator, reminding her that “the older I get, the wider and more broad I understand the world to be, and therefore my Judaism.”

Several groups — including the Chabad-Lubavitch movement’s Aleph Institute, the Orthodox-aligned Jewish Prisoner Services International, and a newer progressive group called Matir Asurim — provide services and resources for incarcerated Jews. Some also serve inmates who self-identify as Jewish, even if they have never converted. But the groups do not tend to facilitate conversions behind bars.

There are several reasons. For one thing, a prison is a nearly impossible place to to arrange the process required under traditional Jewish law. Jewish tradition also demands that converts choose Judaism freely, but incarcerated people are inherently not free and may not have pure motivations for converting. In addition, while incarcerated they would largely not be able to follow Jewish law once converted, a requirement held by some rabbis.

Matir Asurim, founded by Reconstructionist rabbinical students, is less bound by halachic stringencies. But it has not yet overseen any formal conversions, though its spokesperson said it is “in conversation with inside members about best pathways to support their desires for conversion while facing incarceration.”

“On a theoretical level it could be possible,” Rabbi Aryeh Blaut, president and rabbinic advisor for Jewish Prisoner Services International, told JTA. He said a traditional conversion could be undertaken if prisons — not known for being especially accommodating —- would allow the use of a kosher mikvah, or ritual bath, and, for men, a certified mohel to perform an adult circumcision or ritual equivalent.

Blaut’s group has never attempted to orchestrate such a conversion. In part this is because they believe the conditions of incarcerated life, including restrictions on prayer and the difficulty of abstaining from certain activities on Shabbat, make it all but impossible to live a Jewish life behind bars in accordance with traditional Jewish law. He says he advises incarcerated non-Jews interested in conversion to instead follow the Noahide laws, Biblical guidelines for non-Jews given in the story of Noah. He did help one determined individual convert once he was released.

“To convert someone, now they have to keep kosher. But the prison isn’t willing to give them kosher food. What have you accomplished?” Blaut asked. “There’s not a real Jewish community. There’s a handful of federal prisons that may have enough Jews to even have a minyan. How do you even learn how to pray properly if you don’t have a group of people that you can learn from?”

In addition, Blaut said, the motives of incarcerated individuals seeking to convert are important to consider. Some may just “want to give the prison a hard time” by advocating for kosher food even if they don’t have an interest in keeping kosher, he said; kosher food can be a hot commodity in prisons.

Rabbi Miriam Terlinchamp (Courtesy)

Terlinchamp was sympathetic to those concerns and said she was also wary about beginning the conversion process with Kingsman and Phillips. “If you have worked in that field in any capacity, you know that you have to watch out. You have to be careful about who’s using who,” she said. “People call you ‘rabbi,’ they want something from that title.”

Still, Judaism Unbound makes the exploration of nontraditional Jewish practice part of its mission. And Terlinchamp — whose lifelong interest in conversion stems from discrimination she said her father experienced after converting before marrying her mother — felt herself drawn to the cause of “the guys,” especially after hearing how no other rabbi would help them.

Terlinchamp was also drawn to prison populations after seeing friends experience incarceration. “I had a friend in undergrad who went to prison. He’s a physics professor now, he’s a very accomplished person,” she said. “And I remember feeling like the justice system meted out a level of punishment that did not fit, I felt, the crime.” In rabbinical school at the Reform movement’s Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute for Religion in Los Angeles, instead of working in Jewish schools or other common postings for students, she worked with the Jewish population in the Los Angeles men’s jail system.

The show focuses primarily on the converts, Kingsman and Phillips, both of whom had studied Judaism for years before embarking on their conversion process. In prison, they told Terlinchamp, religion offers structure and meaning to what can otherwise feel like a purposeless life.

They both became interested in Judaism despite having had little interaction with Jews in their lives before being incarcerated. Kingsman, who was interested in languages, joined up with a Jewish study group and taught himself Hebrew by reading prayer books and listening to cassette tapes. Phillips says he befriended Jewish inmates who were “having a wonderful time” and decided, “That’s where I need to be.”

“There was a void within me that needed to be filled that I had been seeking for so very long,” Phillips tells Terlinchamp in the podcast, saying that he connected the Jewish value of tikkun olam, or repairing the world, to the principles of restorative justice.

Judaism was also more prevalent at Monroe than in most other prisons thanks to the presence of a dedicated Jewish group, which numbers around 12 people and was spearheaded by a Jewish chaplain who is not a rabbi, Amy Wasser.

“I never really understood why there weren’t rabbis who were willing to convert on the inside,” Wasser said. Religious programming is one of the most widely available options to incarcerated people, and the ones who choose to study Judaism, she says, really mean it.

“These men, they’ve walked this path. They’ve chosen this path. No one pushed them to this path,” she said. “Finding Judaism, finding a religious path that spoke to them, that gave them grounding and support and a spiritual compass, I think that’s been really profound for both of them.”

Wasser, who had her contract ended by the Department of Corrections in May, would ultimately participate in the conversion process, delivering the priestly blessing for Kingsman and Phillips in an experience that she says was “one of the most meaningful things I’ve done in a long time.”

The prison’s Jewish group includes those drawn to Judaism such as Kingsman and Phillips, as well as people who were born Jewish but reconnected with the religion only in prison. But in a sign of just how much this project bucks norms in the Jewish world outside the prison gates, the group also includes Messianic Jews, or people who identify as Jewish but believe in the divinity of Jesus. Though the Jewish group does its best to shut down any conversations about Jesus, the podcast series concludes with a shake-up in the group that leads Terlinchamp to fear that Messianic voices may take over the space.

Searching for Jewish material they could access from prison, Kingsman and Phillips stumbled onto the “Unbound” podcast — which, for reasons no one on the production team can figure out, came preloaded along with thousands of other podcasts on a third-party contractor’s tablet that the federal Department of Corrections has approved for prison use. (“Tales of the Unbound” will likely face greater difficulty in getting such approval, since it is about prison life and the department’s censors, fearing unrest, typically try not to expose prison populations to narratives about incarceration.)

Terlinchamp’s episode, in which she discusses her efforts to expand and demystify the Jewish conversion process beyond its traditional guardrails, stemmed from an online conversion course she had crafted for the Unbound team’s “UnYeshiva” virtual learning series. When she was conscripted into the conversion project, she put those ideas to use, brainstorming with Wasser how to perform approximations of the conversion rituals within the prison system.

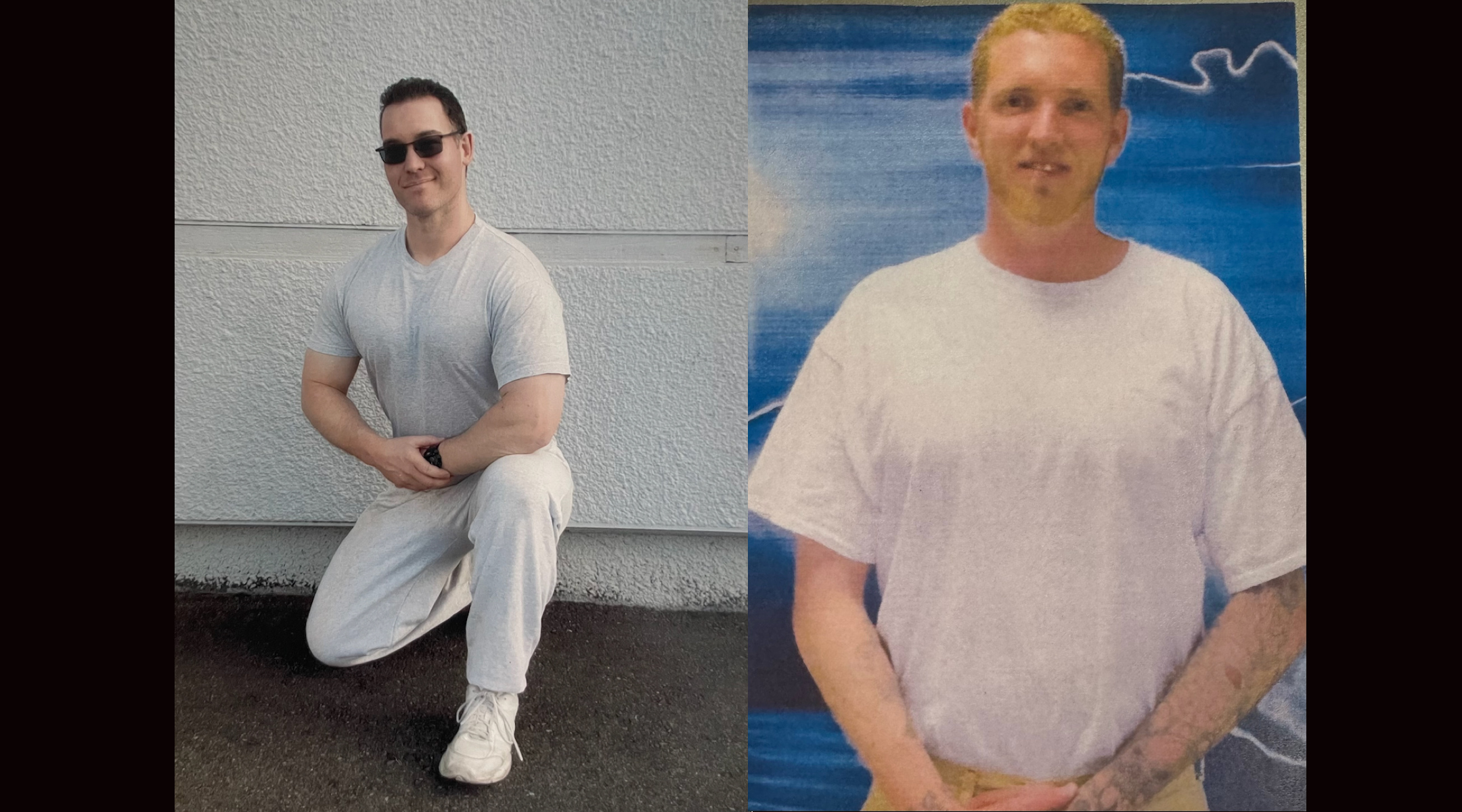

Ari Kingsman, left, and Joshua Phillips both converted to Judaism while incarcerated. (Courtesy of Judaism Unbound)

Those negotiations are a large part of the podcast: Episode 5, for example, explores how Terlinchamp and the men navigated their very different approaches to the conversion ceremony.

“I lean towards more Orthodox practices,” Kingsman says in the podcast. “I want to do everything possible to do it the quote-unquote ‘right’ way, even though there’s several different ways mentioned in the Talmud.”

Terlinchamp, meanwhile, is on the liberal edge of the Reform movement when it comes to conversion, not requiring circumcision even though the movement strongly recommends it. “I have lots of feelings about it, and it was hard for me to understand its importance to the guys,” she says in the podcast. “But in Ari and Josh’s minds, their conversion would not be authentic without tipat dam,” a term for a ritual drawing of blood from the penis for men who had already undergone a medical circumcision.

In the end, Terlinchamp said she kept coming back to her opposition to creating barriers to Jewish experience. “What are the limits to the gatekeeping that we do in the Jewish world? How do we say yes?” she says she asked herself.

So she convened a beit din, or rabbinical court, to supervise the conversions. She also reluctantly agreed to help Kingsman and Phillips undergo tipat dam, also known as hatafat dam brit. And she figured out how to create a mikvah within the prison walls.

But all of the elements deviated from strict interpretations of Jewish law. For the beit din, Terlinchamp enlisted Wasser and her husband Marvin — neither of whom are rabbis. The men self-administered their hatafat dam brit with needles. And the mikvah was converted from the prison’s baptismal bath, filled with rainwater which the team decided was the closest equivalent to the “living water” required by Jewish law.

For Phillips, the conversion process also opened up deeper reflections on his own situation. Sentenced to life in prison under a “three strikes” law after a string of violent incidents (the podcast producers do not discuss their converts’ crimes), he takes one episode to reflect on his culpability, the history of abuse he experienced in his family, and his desire to repair old relationships.

In 2021, he says, he learned about his father’s abuse of his mother as he was also embarking on a journey of restorative justice, all while learning about Judaism for the first time. A relative contacted him to tell him that a genealogical test showed he had some matrilineal Jewish ancestry — a coincidence that compelled him to try to convert.

As Terlinchamp’s relationship with “the guys” deepened even months after their conversion, it also touched on another reason why other rabbis tend to frown on what she did: the prospect that a convert may be embracing Judaism for personal material gain. Last month, at Phillips’ request, she wrote a letter to the Department of Corrections advocating that his life sentence be reduced to 20 years, and cited his conversion work as one reason.

“He took his studies very seriously,” Terlinchamp wrote, adding that Phillips was “making significant contributions to his small Jewish community within Monroe Correctional.” Pointing to the part of the podcast in which Phillips voluntarily shared personal reflections on his crimes, she argued, “Joshua’s understanding of forgiveness is not just theoretical; he embodies it in his actions. His transformation is not solely a result of his changed soul, mental health support, or newfound religious beliefs. Joshua recognizes that it is his deeds that truly matter.”

Terlinchamp told JTA that she felt comfortable writing the letter because Phillips had already been living as a converted Jew for months. “I was writing on behalf of a Jew, not someone in the process of converting,” she said. She added that, in her view, “the material gain isn’t commensurate with the cost of identifying as Jewish,” pointing to the large numbers of white nationalists and neo-Nazis in U.S. prisons. (In the podcast, Kingsman and Phillips describe Jews who were transferred to their prison after being threatened or attacked for being Jewish at their old facilities.)

Terlinchamp ultimately concluded, “The price he pays for being Jewish is way higher than the minimal external benefit of a letter of recommendation.”

Wasser said such a request also didn’t strike her as unusual or untoward. “I don’t believe his path to Judaism was a means for him to be able to tick a box and say, ‘Oh, yes, now I can ask this rabbi to write me a letter saying that I’ve now converted to Judaism, and I’m a better person now,’” she said. “They’re always looking for letters of support.”

As Terlinchamp took stock of the new Jews she brought into the world, she says she knew her own rabbinical practice would be forever altered. In her new role away from congregational duties, she is seeking out other “unbound” Jews in situations for whom she sees her work with Kingsman and Phillips as a test case: queer Jews who feel unwelcome in organized spaces, perhaps, or rural Jews who live nowhere near a congregation and Jews with disabilities who can’t easily access physical Jewish spaces.

It’s possible, she said, that her Monroe Correctional converts may move onto other Jewish communities and leave her behind. She believes that Kingsman, for example, “will fit beautifully in the Orthodox world” when he is released from prison. In which case, she mused, he may choose to seek out a more traditional conversion, because hers — using unconventional means, and overseen by a woman — would not be acceptable in Orthodox communities.

But she’s OK with that. “I think that just because you serve someone in a given stage of their life, and that they then change from it, doesn’t mean they didn’t serve you,” Terlinchamp said. “The whole point is if he gets to be who he wants to be.”