Growing up in Vilna in the 1930s, Yitskhok Rudashevski was a typical 13-year-old Jewish boy living a typical Jewish life: He went to school, spent time with friends and family, read and wrote poetry and got involved in Jewish activities at the cultural center, talking about global politics with his father, who was a writer for the Yiddish daily, called Vilna Tog.

In June 1941, Rudashevski began keeping a diary, documenting the alarming transition — in just three months — from living a happy life under the looming threat of war to his family’s forced move into the ghetto, where comfort, joy, food and personal space were in short supply.

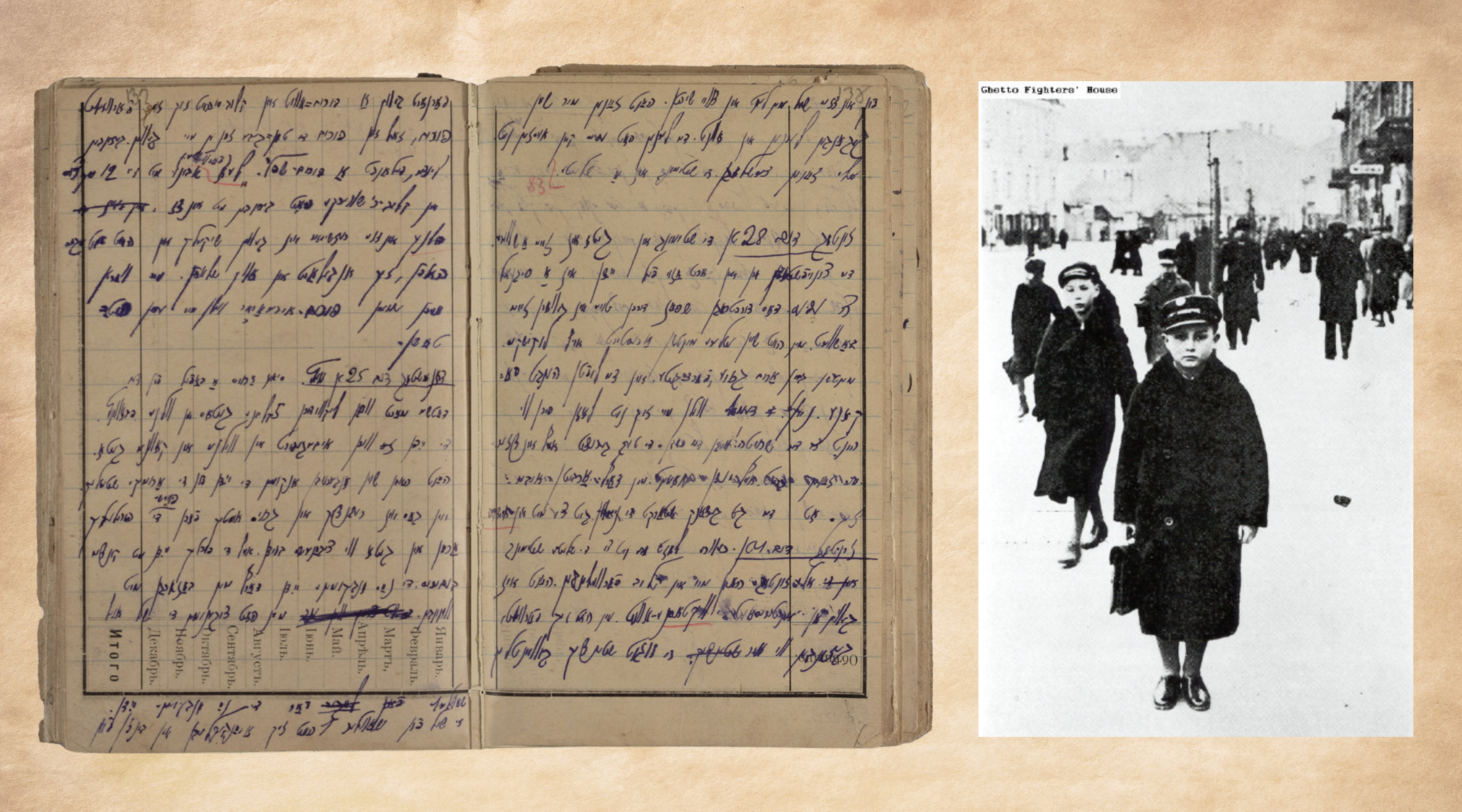

Over the next two years, in neat Yiddish script written in a black notebook, Rudashevski described ghetto life.

His story is now the core of a comprehensive new online exhibit by New York’s YIVO Institute for Jewish Research as part of their free, public online museum. It launched on Wednesday.

The interactive exhibit, which can be viewed in individual chapters and takes roughly two-and-a-half hours to click through from beginning to end, incorporates narrative, text, video dramatizations, illustrations, photographs and more to tell the story of Rudashevski and the Vilna Jewish community. Alongside the diary, translated from Yiddish specifically for this exhibit by Solon Beinfeld, the exhibit gives context to Rudashevski’s life in Vilna and the cataclysm that brought it to an end.

“The online electronic format of this allows us to make use of extensive documentation from our archives that otherwise would be very difficult to put in a single exhibition, and it enables us to tell a story in many different ways,” Jonathan Brent, the CEO of YIVO, told the New York Jewish Week of the decision to put the exhibit online.

“We feel at YIVO that there is an obligation and a responsibility to make our treasures and the immense resources that we have of historical knowledge, for cultural knowledge and for artistic knowledge, available to the widest possible group of Jews of Ashkenazi descent,” he added. “And not just of Ashkenazi descent, and not just Jews. This also gives us a way of reaching Lithuanians in Lithuania and Poles in Poland.”

Yitskhok Rudashevski, lower left, with his arm around his mother, Rosa, poses with his parents and grandparents. His father Eliyahu is at top left. (Courtesy of Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum, Israel/Photo Archive)

Rudashevski’s diary — which has been kept at YIVO’s Manhattan headquarters since 1946 — illuminates the quotidian daily life of the Jewish community in Vilna and what the children and adults were thinking about and focused on. Much of his diary, like any middle schooler’s, talks about his homework assignments, friendships and daily schedule.

Other entries shed light on the devastation and desperation Rudashevski felt at how quickly his life changed. On Sept. 6, 1941, the day Rudashevski entered the ghetto, he writes:

A ghetto is being created for the Jews of Vilna. At home we are packing. The women go around wringing their hands, weeping as they see their homes looking like after a pogrom. I walk around, weary from lack of sleep, among the bundles. I see how overnight we are uprooted from our homes. Soon we get a glimpse of the first image of going to the ghetto. It is an image from the Middle Ages. A big black mass of people moves, harnessed to their big bundles. We understand that it will soon be our turn. I look at the disorderly room, at the bundles, at the overwhelmed, despairing people. I see things lying around that had become so dear to me, that I used to use. Soon two Christian neighbors [arrive to look at our room]. We carry the bundles into the courtyard. On our street a new mass of Jews keeps streaming to the ghetto.

By September 1943, the Nazis liquidated the ghetto and Rudashevski and his family went into hiding in the attic of a building. They were soon discovered and murdered a few weeks later in the nearby Ponar forest. His cousin, Sore Voloshin, who was able to escape and was the sole survivor of the family, found the diary in the attic after the war ended.

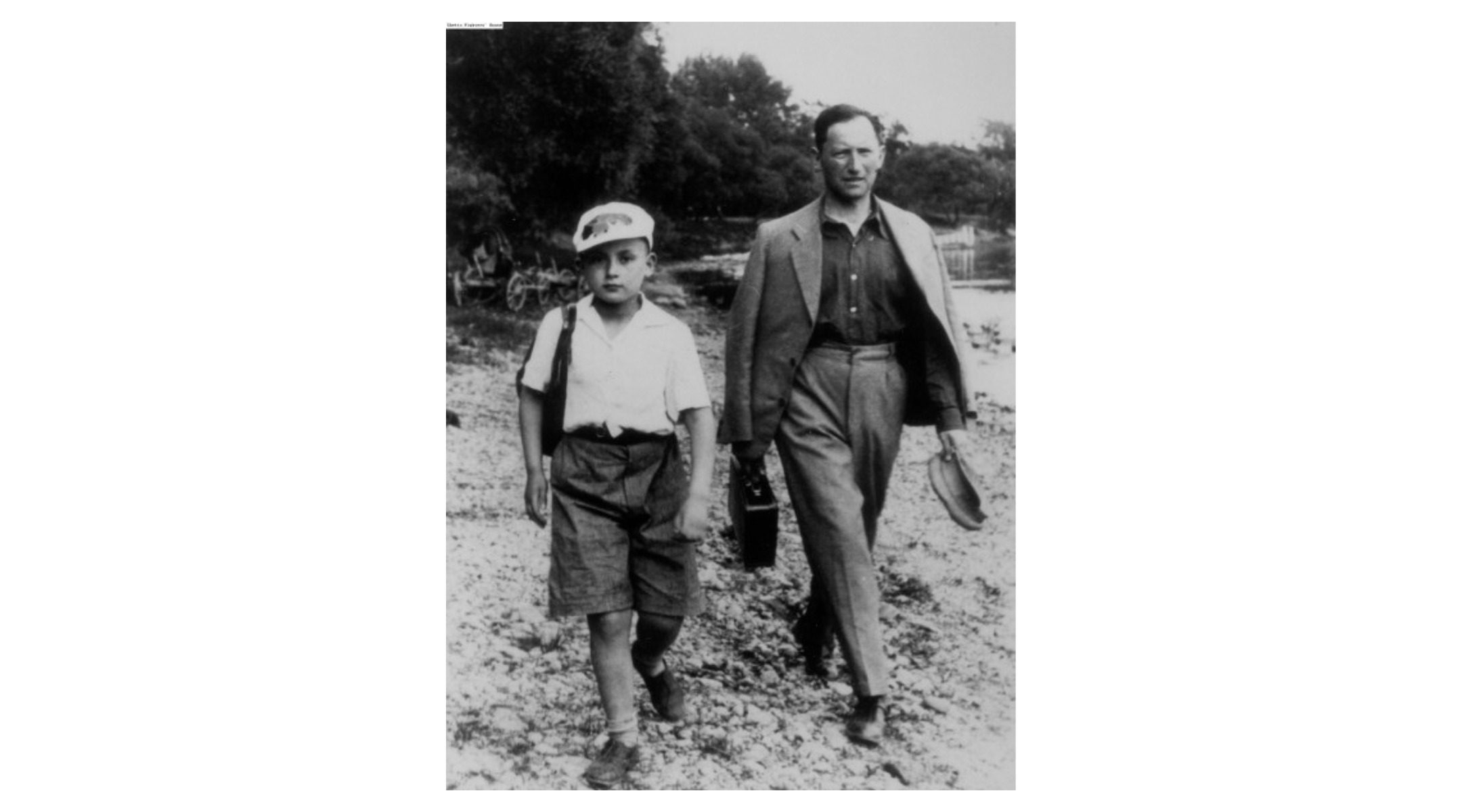

Yitskhok Rudashevski and his father Eliyahu in the 1930s. (Courtesy of Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum, Israel/Photo Archive)

Voloshin turned her cousin’s diary over to the Yiddish poets Avrom Sutzkever and Shmerke Kaczerginski, who sent it to YIVO in New York City in 1946 as part of their effort to preserve what was left of Jewish culture in Eastern Europe. The diary was published in Yiddish in the 1950s and had been incompletely translated before. This is the first time YIVO is highlighting the diary in its own exhibition as opposed to a portion of a separate exhibition.

Support the New York Jewish Week

Our nonprofit newsroom depends on readers like you. Make a donation now to support independent Jewish journalism in New York.

This is the second online exhibit curated by YIVO — in 2020, the museum published a similarly curated exhibit about Beba Epstein, a Lithuanian and secular Jewish teenager at the time of the Holocaust. In 1934, Epstein wrote an autobiography, which was among hundreds of thousands of documents in YIVO’s archive that were rediscovered in 2017, having been smuggled out of the Vilna ghetto by the “paper brigade,” a group of Jewish poets and scholars who preserved the documents.

YIVO hopes an online exhibit like this can be used for educational purposes and throughout the exhibition has curated resources to guide teachers on how to use it in classrooms.

Brent, himself a historian, said the diary is unique because it showcases how committed the Jewish community of Vilna was to Jewish life and how that commitment was entrenched in every moment of living in the ghetto.

“The thing that blew me away in reading this diary of this 13-year-old boy was his strength and spirit. He is aware of the fact that by reading the poetry of Yehoash or of [I.L.] Peretz or other great Yiddish writers, by virtue of doing that, he is performing an act of defiance and resistance against the Nazis,” Brent said. “When Jews study our past, we get teeming information about death. What this diary provides is information about life.”