(JTA) — When I reached Nimrod Novik in Raanana, Israel and asked how he was feeling, he was blunt.

“Bad,” said Novik, 77, who was a senior policy adviser to the late Israeli Prime Minister Shimon Peres. “I’d say that I don’t remember such a decisive moment. We are at a fork in the road, which can take us to untold troubles or potentially promise a new horizon. I’m afraid that we’re going to slide in the wrong direction and pay the price for it before we wake up to it.”

So Novik is no Pollyanna. But with war raging in Gaza, he is looking beyond the fighting for a pathway toward a diplomatic solution that could lead to two states, Israeli and Palestinian. It’s a decades-old vision that more than one politician, including Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, has called dead on arrival.

In 2021, as a member of the executive committee of Commanders for Israel’s Security, Novik was part of a team of former security chiefs, military brass and top government advisers who wrote a defense of the two-state solution called “Initiative 2025.” The document said that even though such a solution seemed beyond the horizon, it remained the only way to ensure Israel’s security and future as a strong Jewish democracy.

Novik is sticking to those conclusions despite an Israeli government that is opposed to Palestinian statehood, and polling showing that just 35% of Israeli Jews support a two-state solution. The Biden administration is also pressing for an eventual two-state outcome, in a plan that could potentially include normalization between Israel and Saudi Arabia.

In our conversation, I wanted to know: Given the distrust, the bloodshed, the current mood of Israelis, the far-right policies of their government and the past failures of negotiations toward two states, how does any politician build a coalition and public support for anything less than an iron fist in Gaza and a tighter grip on the West Bank?

Novik, a fellow at the Israel Policy Forum, answered by describing the self-interests of Israel and its Arab neighbors, the frustrations of average Palestinians, a new role for the Palestinian Authority in Gaza and the grim alternatives for Israel if the two sides in the conflict are unable to separate.

Our conversation was edited for length and clarity.

Novik, a fellow at the Israel Policy Forum, was part of a team of former security chiefs, military brass and top government advisers who wrote a defense of the two-state solution called “Initiative 2025.” (Israel Policy Forum)

I was eager to talk to you because there is a camp, which includes the Biden administration, that wants — at long last — a two-state solution to come out of this war. With all the destruction and anger and bloodshed we’re seeing, isn’t it crazy for anyone to be pressing for two states, in the short or long term?

It’s not crazy at all. Since Oct. 7, the awareness that the past premises were all wrong is widespread. I think you will find a broad consensus in the country that relying on Hamas for 15 years to provide peace and quiet for Israel by feeding the beast piecemeal, and giving concession after concession, and allowing it more money from Qatar — that strategy failed.

I believe the term in Israel for that was “mowing the grass” – military strikes in Gaza every few years to quash Hamas missile attacks. In the interim, Hamas would keep the peace and Qatar would funnel the money. You are saying that any two-state solution first needs to address who is going to govern Gaza.

Right. I belong to Commanders for Israel Security, which is today something like 550 former heads of all the security agencies and the diplomatic corps. And our suggested plan, described in [the 2019 document] an “Alternative Israeli Strategy in Gaza,” is now basically the Biden strategy. Basically, we were working with the Egyptians to bring in the Saudis and Emiratis to make Qatar less dominant in controlling the lifeline of Hamas, so that the money goes to the population, not to the organization.

Second, the Hamas leadership, which is the same today, had a vivid memory of the Arab Spring, and feared facing a similar uprising in Gaza. They had demonstrated that they were unable to deliver for the people, had not mastered the art of governance and became corrupt. They were seriously concerned that they will lose the only territorial entity controlled by Muslim Brotherhood [the Islamist movement of which Hamas is an offshoot] anywhere in the world, which is so valuable to those who hold that ideology.

The Egyptians were astonished that they were willing to cooperate with a strategy whereby Hamas withdraws from governing the street and invites the Palestinian Authority to man the ministries of government and run the place. There was a whole roadmap for the gradual steps that would lead to the Palestinian Authority’s restored management of Gaza. We developed it jointly with the Egyptians and we were in contact with Saudis, Iraqis and even with the Trump administration in Washington. [Trump aide] Jared Kushner and [U.S. special envoy] Jason Greenblatt went to Cairo for a presentation of the plan and Greenblatt made a public announcement that it’s time for the Palestinian Authority to come back.

What did the Israeli government think of the plan?

Benjamin Netanyahu had given a green light to the discussion but had a change of heart and was sabotaging the plan. And the plan was just discarded and became a footnote to history. But it’s the exact same plan that is now being constructed by the administration in Washington, only under, on the one hand, more favorable conditions, and, on the other, more complicated.

What are the favorable conditions?

There is a very powerful Arab coalition that is more willing to engage in this endeavor. The Arab coalition is willing to engage in Gaza rehabilitation and serve as the crutches while the Palestinian Authority is in such a miserable state, and help the P.A. gradually come back and run the Gaza Strip, fund the rehabilitation and reconstruction and even put boots on the ground to replace the IDF until the Palestinian Authority can train and equip new units.

Why are they more amenable to that now?

They too were awakened to a wrong premise: that one can pay lip service to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and live happily ever after. Oct. 7 demonstrated to them that their strategic interests, security, and internal stability are affected by violence in the Israeli-Palestinian arena. So Saudi Arabia, which used to be quite passive, are now willing to engage in diplomacy, managing Gaza and revitalizing the Palestinian Authority. They were all so tired of the P.A. until Oct. 6. Now they realize that being tired is not an action plan.

Another myth was that you can leapfrog over the Palestinians into the arms of the Arabs around the region like in the Abraham Accords.

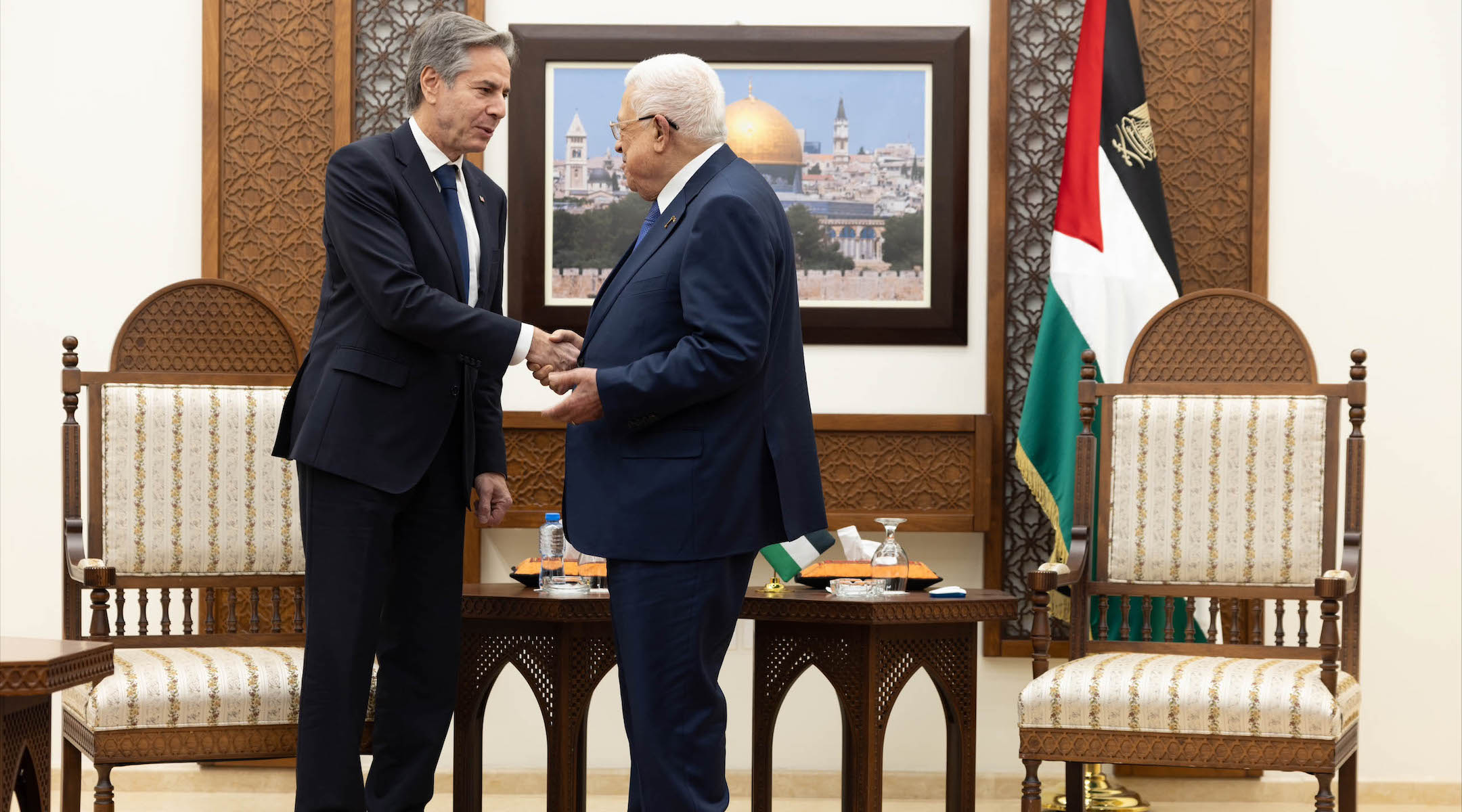

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, right, meets with U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken in Jerusalem, Jan. 9. 2024. (Kobi Gideon/Government Press Office)

The Abraham Accords were the historic normalization agreements between Israel and several of its Arab neighbors brokered starting in 2020. What is the Arab states’ interest now in supporting P.A. control in Gaza as well as the West Bank, if they weren’t actively pressing for it before?

They realize that they need to see a change on the ground, both because of the damage caused by these four months of war to their interests and because they don’t want to be in a situation where they engage in Gaza rehabilitation and West Bank development and all of that goes up in flames in the next war between us and Hamas, or one is triggered by our lunatics on the Temple Mount or by extremists on their side in the West Bank. So they want to see a peace process of sorts, and a more credible one. And even if the authority given to the P.A. is only symbolic, it will give legitimacy to whatever third party walks into the West Bank to start working there.

And there is a new mantra now in the region. People don’t talk about the Palestinian Authority anymore. We talk about the RPA, the “revitalized Palestinian Authority,” and that’s copyright President Biden.

And there is a second mantra, and it is long: the entire Gaza and West Bank process is to be conducted on the basis of a “concrete, time-bound, irreversible path to a Palestinian state.” So you have your qualifiers — concrete, irreversible, timebound, path — each one of which was given a lot of thought.

So far we are talking about what Arab states and perhaps Washington wants for the future. But what about Israelis? Netanyahu is adamant that Israel doesn’t want a two-state future and in the case of the settlements is actively working against it.

The unthinkable brutality on Oct. 7 did not produce an urge for it, but stay tuned. In all studies that I’ve seen, Israelis are saying — which is perhaps surprising — that force alone will not give us stability. In order not to give up security we need a combination of strength and diplomacy. In Israel, the term “political arrangements” is the new substitute for “peace agreement,” which lost all legitimacy for now. People wish to see a combination of diplomacy and strength which gives an alternative leadership a lot to work with, should they wish to.

Is that alternative leadership on the horizon? Because after events like these, you would think people would get more frightened, more right-wing, less open to, you know, political arrangements.

It’s too early to draw definitive conclusions but what we saw over the last four months is not necessarily how it really will evolve. When I look at the last four months, we are in phase three of the collapse of public support for the current leadership. Phase one was the nine months preceding Oct. 7 when 65 percent of the public opposed the government’s [judicial overhaul] initiative. Phase two was obviously Oct.7. itself, when the most common characterization was “abandonment” — abandonment by the army, and abandonment by the government. And the third phase was post-Oct. 7, when the government was missing in action, and it fell on civil society to deal with the needs of those affected, including the relatives of those who were kidnapped or killed or those who were evacuated from the south and from the north.

The visible result of those three phases is the collapse of the current coalition in the polls. The current coalition mustered a 64-seat majority in the [120-seat] Knesset. Now it’s about 44-45 [in polls], while the opposition is way over 70. I’m not suggesting that if elections were held tomorrow these would have been the results, but I think that the current coalition is done.

And the fact is that the most extreme right has not gained a single vote since Oct. 7, with all the anger and fear and despite an unprecedented rise in hate for Arabs, Palestinians and Israeli-citizen Arabs.

I am thinking of the American Jew who felt the two-state solution was inevitable but now feels listen, if you risk turning any of these territories over to Palestinian leadership, you are just inviting another Oct. 7. Why would separation make Israel safer over the alternative, which is military domination over both territories?

I think it will take time, but what I think is the true message of Oct. 7 is that anger is not a very good advisor. Oct. 7 demonstrated the price of “managing the conflict.” If we do not change course, if we end with a prolonged occupation of Gaza, we’re going to see a Gaza-like situation in the West Bank. The moderates will lose residual ground to extremists.

It is no accident that 10 years ago, the P.A. was very popular and Hamas was totally unpopular on the West Bank. And today it’s the reverse, particularly among the younger generation. Why? Because 10 years ago it looked as though the Palestinian Authority might be the vehicle for independence, and instead the P.A. turned into a subcontractor of Israeli occupation and lost all credibility with its own constituency. And suddenly the only one they see doing something against the occupation is Hamas, so they became very popular.

So now the IDF is going to reoccupy, and we’re going to run the lives of 3 million people in the West Bank, over 2 million people in Gaza, with no exit strategy? Now, are these people likely to roll over and play dead? Or are they going to resist the occupation by the only means available, absent the peace process, which is violence?

Will the Arab countries that signed peace deals with us be able to resist public pressure to walk away, be it Jordan, be it Egypt, be it the [signers of the] Abraham Accords?

Blinken meets with Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas in Ramallah, West Bank, Jan. 10, 2024. (Official State Department photo by Chuck Kennedy)

What is the alternative?

On the other end of the spectrum, we are invited to be integrated into a regional security structure vis a vis Iran along with all those countries that are willing to come in and help on Gaza or a peace process with the Palestinians, however long it might take, and join forces with us to check Iran’s meddling in the region directly and via its many proxies.

That’s why I say we are now at a crossroads. Certain facts have not changed since Oct. 7, and one is that between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River there are 7 million Jews and 7 million Arabs. Either we separate or we lose our identity, or we give them equal rights and we’re no longer Jewish [as a state].

Or we deprive them of equal rights and become non-democratic. But they will not forever agree to live deprived of rights. They will fight and we will bleed, until we bleed each other into separation.

So in my judgment, separation is inevitable.

Your colleague at the Israel Policy Forum, Michael Koplow, has written that if the United States and the Europeans recognize a Palestinian state without first working out the details it “will backfire with Israelis, will backfire with Palestinians, and will make a two-state outcome more rather than less remote.”

If recognition of a Palestinian state comes out of context, it will make people in Washington and elsewhere feel good about themselves. But it would do nothing for Palestinians, because in general they are done with gestures. And the reason that the younger generation, which doesn’t carry the scars of the Second Intifada like their parents, advocate violent resistance rather than political resistance, is because the younger generation doesn’t believe the situation will get any worse.

Meaning a credible path toward a two-state solution gives them something to lose, assuming they or their leadership are willing to accept less than the river to the sea.

In one situation, the terrorist is the hero of the neighborhood because he’s the only one who stands up to the occupation. In the other situation, the same terrorist in the same neighborhood risks what they have gained in independence. Will they help him get safe haven, or are they going to snitch on him in order not to lose?

Will the young Palestinian who can suddenly go abroad, can go to university, sees his life changing, sees his dignity restored — will he risk it because the extremists have a different vision?

I want to return to the security question — what assurances can you give an Israeli who says the risks of the inevitable future you see are worse than the current arrangement?

It’s a very serious question and I would answer it with the question Begin raised before he agreed to withdraw from the Sinai in order to have peace with Egypt: In the worst-case scenario, will we be able to rectify the situation at a reasonable cost? Are we going to be okay? And he was persuaded by the defense professionals that the answer is yes.

This same question has to be asked about Palestinian statehood. If worse comes to worst, if this Hamas or another Hamas wins elections in a post-peace Palestine and decides that it is not satisfied with less than everything, are we able to rectify the situation at a reasonable cost? We spent a year and a half with a huge team of all disciplines with thousands of years of experience around the table in developing security arrangements for that eventuality.

And again, always the bottom line is we don’t do it because we trust them. We do it because it serves our vision of Israel.