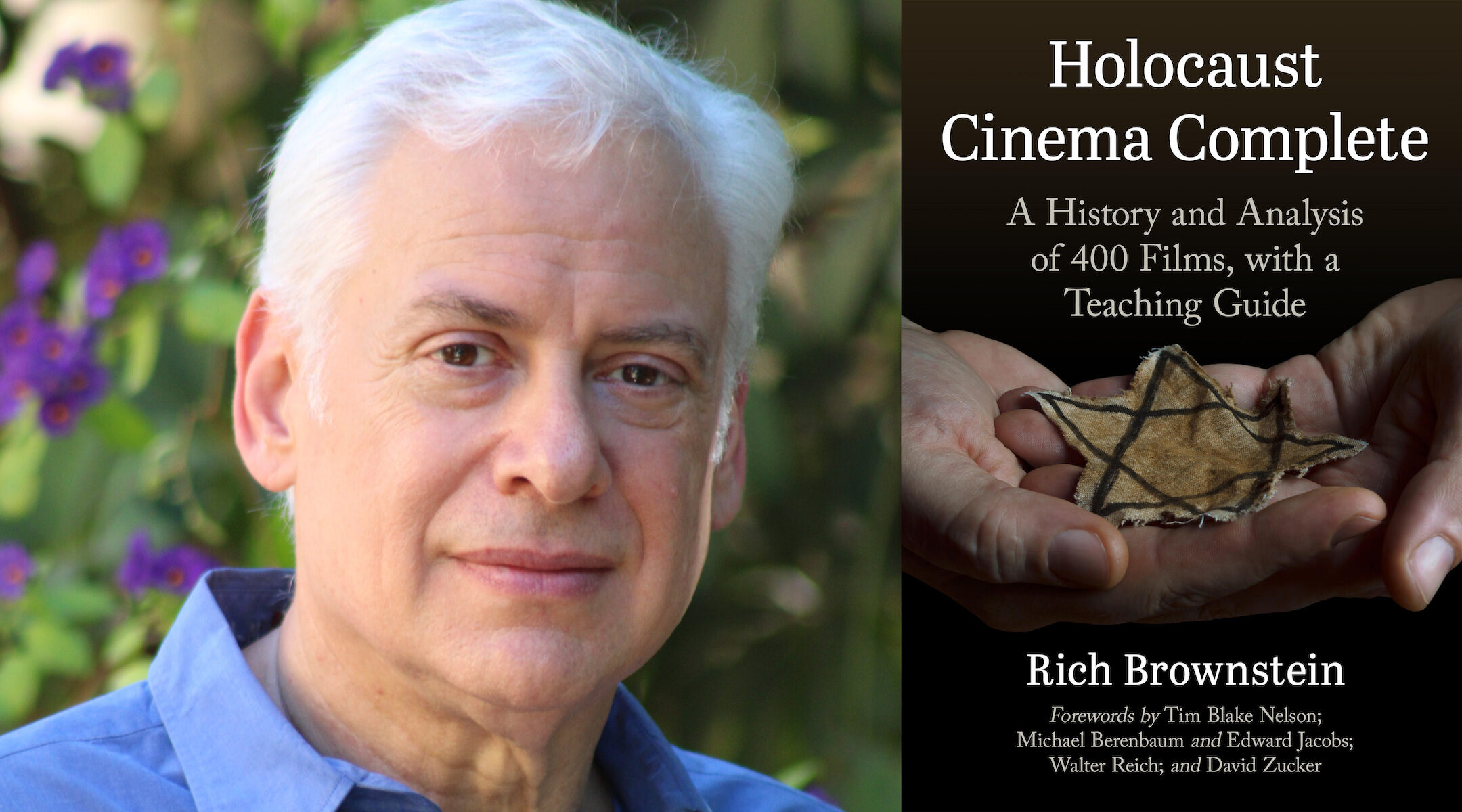

(JTA) — At least 440 narrative films have been made about the Holocaust — and Rich Brownstein has seen just about every single one of them.

As a lecturer on Holocaust film for Yad Vashem’s international school, Brownstein has both a personal and professional interest in viewing and cataloguing so many depictions of Jewish suffering.

“Dealing with Holocaust education is akin to dealing with oncology, in that you have to set aside your personal feelings,” he says. “You can’t be drawn in.”

Now, Brownstein has published “Holocaust Cinema Complete”, a comprehensive book-length guide to the ever-expanding cinema of the Shoah. The book, which went on sale in September, contains statistics on the content of the films, essays on their methods, descriptions and capsule reviews and information for educators looking to use Holocaust films in their curriculums. Documentaries are not included, but made-for-TV movies and miniseries under three hours in length are.

Brownstein says he has seen “every film that is available to be seen” (excluding unreleased outliers such as Jerry Lewis’ “The Day The Clown Cried”). In the book, he gives his unvarnished opinions on the giants of the genre, including “Schindler’s List,” “Life is Beautiful” and “Jojo Rabbit” — and fans of those movies may not like what he has to say.

We want to hear from you! Fill out this survey to tell us which Holocaust film you think everyone should see.

Born in Portland, Oregon, Brownstein hasn’t always focused on such dour subject matter. Prior to moving to Israel in 2003, he worked as a producer for Jewish comedy legend David Zucker (“Airplane!”) and “South Park” creators Matt Stone and Trey Parker (Stone is Jewish), even appearing in an uncredited cameo in the trio’s 1998 comedy “BASEketball,” before founding his own video transcription company. He says he has no familial connection to the Holocaust, and first became interested in the subject after reading Leon Uris’ novel “QB VII.”

Brownstein spoke to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency about his years watching Holocaust reenactments, what qualifies as a “Holocaust movie” in his book and how the public, and educators, should approach the genre. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

JTA: How did you become drawn to catalogue these films?

Brownstein: I started collecting movies when I was in my twenties. In Los Angeles, I had over 1,000 movies on VHS, and I knew VHS wasn’t going to exist anymore. So I started over on digital, but the whole time, I kept a database, and in the database I had created I would separate Jewish and Holocaust films from others. So I was always attuned to it.

After I moved to Israel, I had a cousin who was on a Young Judea [year abroad] course. And I asked her what she was learning and she said, “We have a Jewish film class. We just watched ‘Private Benjamin’” [a 1980 comedy starring Goldie Hawn as a grieving Jewish widow who enlists in the Army]. I said, “‘Private Benjamin’ is not a Jewish film. It has a Jewish character, but that doesn’t make it a Jewish film.” I happened to have known the educational director for the program — he and I grew up in Portland together. And so I went to him and said I would teach a class for free, on Holocaust films. And he said, “Fine, free is a very good price.”

And then, my daughter was a high school senior, and most Israeli high school kids used to go to Poland on their class trips, and she was the spokesperson for her class. Someone asked her if she would represent the State of Israel at Yad Vashem, at their international conference. I looked at the program, and one of the seminars that they had was on using the documentary “Shoah” in the classroom.

I called up the director, whom I did not know, and said, “I think this is the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard, that you would consider using a 10-hour documentary in a classroom. Students would fall asleep. To have a symposium where you’re advocating to people using ‘Shoah’ pedagogically is reckless.” And he said, “You sound like you know what you’re doing, so we’ll try you out [on a class].” And his blurb is on the back of my book.

Why do you think there are so many Holocaust films?

Well, I actually don’t think there are that many Holocaust films. I think that in terms of the total number of WWII films, for example, it’s a tiny fraction. We just know about Holocaust films because 25% of all American-made Holocaust films have been nominated for an Academy Award. And from 1960 through 2015, every other year, one of the best foreign language films nominated [at the Oscars] was a Holocaust film.

So you think that they’re coming at you like snowflakes in a blizzard, but they’re not. They’re just very well targeted and very well marketed, and we have a hunger, especially in the Jewish community, for this story to be told properly.

I think that the percentage of good Holocaust films is far greater than the percentage of good non-Holocaust films. That is, I think that if I’m recommending 50 Holocaust films in my book, out of 450, that means I’m recommending 11% of Holocaust films. I couldn’t recommend 11% of non-Holocaust films.

You use a categorization system in the book. Can you break it down for us?

You can’t compare apples to oranges; you have to compare apples to apples. I created these categories — it’s a grid. The first [box] is “victim film.” So if a film took place during the Holocaust and it was principally about a Jew, then it’s a victim film, and there are like 100 of them. If a film took place principally during the Holocaust and it’s about a Gentile saving Jews, then it’s a “righteous Gentile film.” If it’s after the Holocaust and it’s primarily about a survivor, then it’s a “survivor film.” After the Holocaust and mostly about a perpetrator, a Nazi, then it’s a “perpetrator [film].”

And then I had a little bit of a problem with with this general theory because of “Sophie’s Choice” and “Inglorious Basterds,” which don’t fit into any of these categories but clearly are Holocaust films, so I added a miscellaneous or tangential category.

You consider “Harold & Maude” and “X-Men” to be Holocaust films. Is anything that references the Holocaust a Holocaust film?

No, not at all. There are many, many films that aren’t Holocaust films in my eyes that other people think are. The most famous ones are “The Book Thief” [a 2013 drama about a young girl in Nazi Germany who steals books to share with a Jewish refugee] and “The Sound of Music” [the famous 1965 musical about a wealthy family in prewar Austria, in which several characters are Nazis], neither of which I consider to be Holocaust films.

“Harold & Maude,” if you think about it, she lives in a train car. And there’s a scene where she’s in the train car with Harold, and he points to the umbrella over her hearth, and she says, “That was when I was a kid in Vienna,” and she’s tearing up. And then she says, “But that was all before.” She’s clearly a survivor, and then they reveal the tattoo. It’s not just that she happens to be a survivor and Hal Ashby threw that in there. Her entire being is shaped by her experience.

“X-Men,” too, not that it’s a great film, but you don’t have “X-Men” without Magneto suffering in the first three minutes, in Auschwitz. The mutants are a metaphor for Jews during the Holocaust, and it’s not a hidden metaphor. Magneto rips down the gates of Auschwitz! Of course it’s a Holocaust film.

JTA readers already know that your favorite Holocaust film is “The Grey Zone,” a 2001 drama about the Jews who worked as “Sonderkommando” at Auschwitz-Birkenau. What are your least favorite Holocaust films, and what distinguishes a bad Holocaust film?

It depends on how far down into the sewer you want me to go, because there are some that are spectacularly horrible.

Kate Winslet in “The Reader.” (Screenshot via The Weinstein Company)

Let’s talk about “The Reader” [a 2008 drama, based on a novel by Bernard Schlink, that won Kate Winslet an Oscar]. “The Reader” is a story about an East German woman after the war, who is really, really hot. But she can’t read. And so she makes this really sketchy deal with a young man, that if he reads to her, they can have sex. And then we find out, after all of this hot sex, that this really nice lady was a Nazi guard, who had, with other women Nazi guards, locked 300 Jews in a barn and burned it down. And she gets put on trial. But she can’t adequately defend herself, because she’s illiterate, and we’re supposed to feel bad for this woman who killed 300 Jews in a barn, because she’s illiterate. That’s really weird. That’s a bizarre notion.

“The Boy in the Striped Pajamas” [a 2008 British drama about a child of a Nazi guard who befriends a Jewish boy held prisoner in Auschwitz] is the same idea… It was an absolute train wreck. It was just a terrible, terrible, terrible movie.

The glorification of Nazis, I’m going to say, the humanization of barbarians is a hard no for me. I’m gonna hold the line there. And that’s my main complaint about “Schindler’s List.” Oskar Schindler was a repulsive, repugnant, horrible human being while the first five-and-a-half million Jews were killed. He didn’t care; he participated. And then all of a sudden, he grew a conscience, so he became a normal person. He didn’t become a good person. You would think somebody who was a cog, who had been participating with the Germans since 1936, that guy doesn’t get elevated.

I know this is an incredibly difficult thing to hear and say, but almost every Holocaust film that ever came out of Canada, and was directed by a Canadian, there’s not a one of them that I can recommend. Every single one of them is horrible.

Your book is structured partially as a teaching guide. In general, how do you think Holocaust films should be used in educational settings?

Holocaust film should be a supplement to lessons. If you are teaching the Holocaust using Holocaust films, then you should rethink your teaching methods, because they are not the beginning of Holocaust education. They are the end of it.

So, if you want to teach about what happened in Birkenau, you can, if your students are old enough, mature enough, you can show “The Grey Zone.” But not before you’ve spent weeks explaining what this place is, and the history of it.

Stanley Tucci and Kenneth Branagh in “Conspiracy.” (Screenshot via HBO Films)

You can teach about the Wannsee Conference, and you can show the film “Conspiracy” [a 2001 made-for-TV drama about the planning of the Final Solution] — a wonderful film, with Kenneth Branagh and Stanley Tucci. It’s one of the finest films I’ve ever seen. But if you don’t know what they’re talking about, then it’s a complete waste of time.

What would you like to see filmmakers and audiences keep in mind when it comes to making, or viewing, Holocaust films?

Well, let’s establish from the beginning that every [historical] narrative film, Holocaust or otherwise, whether we’re talking about “Lincoln” or “Argo” or “Apollo 13,” is a fictionalized account of something that happened. Every narrative film is fiction. If the intention is to represent something true, that happened, then it is raising the bar, and you need to be able to ascertain what elements of the truth are relevant and what are irrelevant.

There’s a difference between watching “Inglourious Basterds” and watching “Schindler’s List.” Everybody should know, after watching “Inglourious Basterds,” that Adolf Hitler was not killed in a movie theater by Ryan the temp from “The Office.” But you don’t know when you’re watching “Schindler’s List” that Jews were not marched into a dual-purpose shower that actually did have water, but that was hermetically sealed, and that the Jews, going in, actually thought that they might be gassed. The misrepresentation of the shower scene in “Schindler’s List” is so egregious that it ruins the veracity of the film.

The second thing is within the context of all filmmaking, where does it stand? Do I need another one of these? Every story has been told, basically. We all know, within general strokes, what’s going to happen. There aren’t a lot of alternatives — people live or they die. But are they going to tell a new story in a new way?

I have to make this really clear: When I sit down to any movie, Holocaust or otherwise, I am the most optimistic person in the world. I want the movie to succeed. I believe in everything that I’m watching until they make me disbelieve it. And even then I sit there and I try to find some reason to like this movie.