(JTA) — Is it appropriate to call an ancient rabbi a “legendary hottie”? To use “thirst” in the online sense? To translate one Talmudic voice replying to another as, “Oh my God, what the actual f–k is wrong with you, you misogynistic ageist dips–t”?

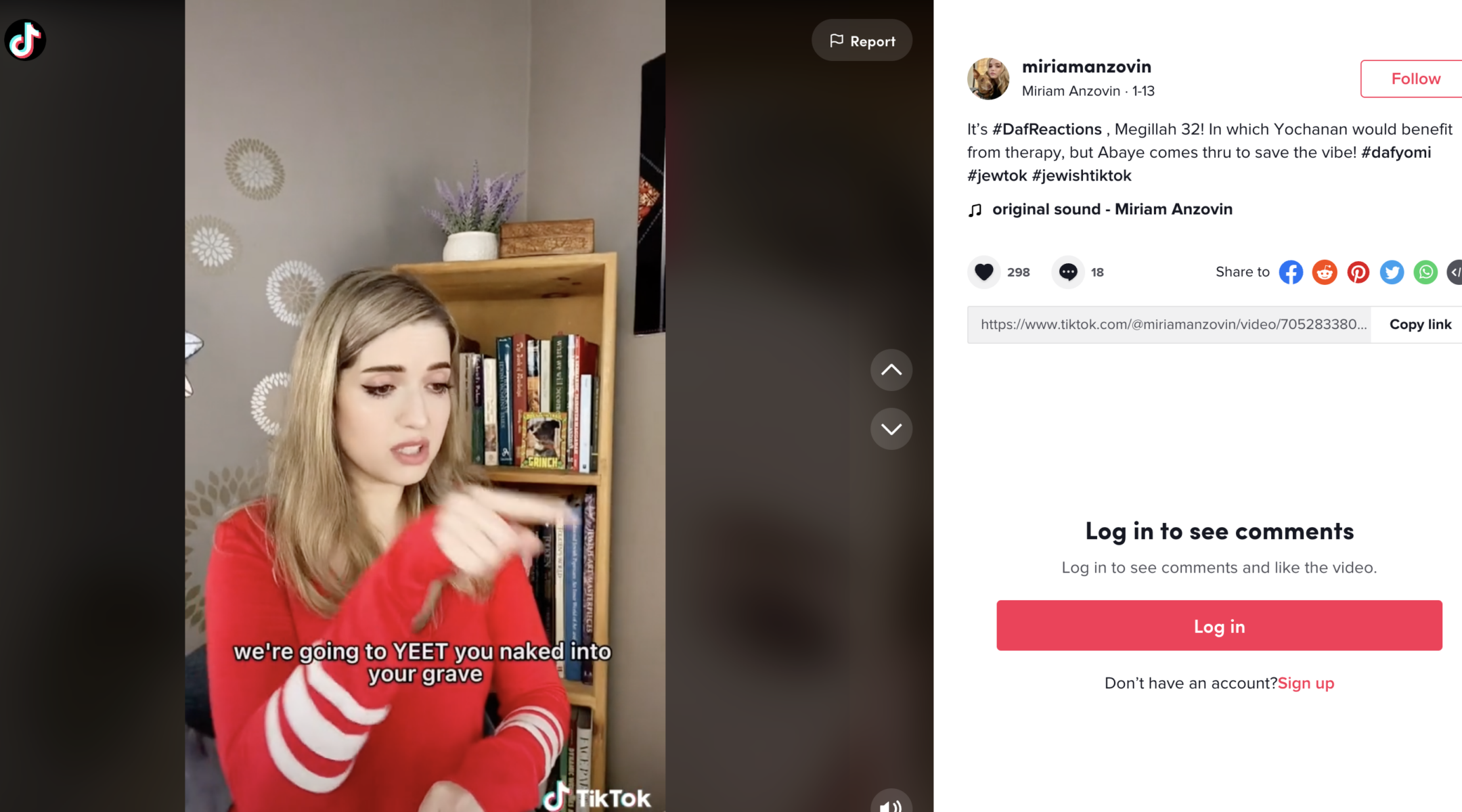

Miriam Anzovin, an ex-Orthodox artist in Boston, ignited debate over those questions this week after making headlines in both North America and Israel for her series of TikTok videos responding to passages in the Talmud, the central text of rabbinic Judaism.

Anzovin’s way of talking about Talmud has been shocking for some. “This is a particularly provocative and crude use of texts sacred to Judaism to rake in likes,” tweeted Avishai Grinzaig, a prominent Orthodox activist and writer in Israel. “This is not traditional, this is not religious continuity, this is not accessibility. It’s just a disgrace.”

Even among fans, Anzovin’s work is frequently praised as a pedagogical tool, useful to get more people engaged in Talmud study but still a sideshow or stepping stone to the more serious study that takes place in study halls and yeshivas.

But for many others, including me, Anzovin’s work is a natural outgrowth of something much larger: a new way of talking about Jewish texts and holy scripture that has come of age with the internet. Despite flying under the radar for many traditionalists, this form of communication about Torah is already fully developed, and it is time for it to be taken seriously as a genuinely new way of engaging with Jewish ideas.

The method of engagement is widespread but does not yet have a name. It draws on “shitposting,” a term that originally referred to insincere and intentionally inflammatory remarks but has since been adopted by many affinity groups — of urban transportation, of Star Trek and of Torah — to refer to a method of discussing ideas that oscillates rapidly between sarcasm and sincerity and doesn’t treat foul language or off-color humor as out of bounds. Though I have participated in such groups for years — Facebook’s “Shitpost the Beit Midrash” group is a personal favorite — until seeing Anzovin’s videos I had never put much thought into how these conversations were supposed to fit into the grander narrative of Jewish discourse.

This kind of discourse is easy to find if you know where to look. On both Facebook and Twitter there are an endless number of well-populated groups and accounts dedicated to Torah memes; as Anzovin’s viral fame makes clear, TikTok, too, is an emerging frontier for this content. Content in these groups is irreverent by default; it frequently contains profanity and sexual innuendo and is not afraid to criticize even the most respected rabbis.

Someone unfamiliar with the tone of these groups might think that contributors are disdainful of Judaism or even on the verge of leaving it behind entirely. But this could not be further from the truth: Many contributors are rabbis and Jewish educators, and they are extending one of the oldest components of Jewish discourse: criticism.

Criticism of Jewish texts is nothing new; the first critic of the Bible is other parts of the Bible. The Talmud itself actively encourages interrogation of even the most sacred texts; one well-known story relates that the sage Rabbi Yochanan was deeply saddened that his study partner kept agreeing with his interpretations. Medieval commentators put each other down with invective that still seems harsh today; decode a page of the Talmud and you will quickly discover a war zone.

Today, students of Jewish texts are still taught to question everything they study, and these questions are frequently the seeds from which additional insights into the Torah grow. It is not a stretch to say that the entire edifice of Torah study would crumble if criticism were forbidden. It is foundational.

In the modern era, this tradition of criticism has taken on a new urgency because it is, for many people, what allows them to maintain a relationship with texts that can feel in turns misogynistic, homophobic and obsessed with ritual minutiae. When Leviticus says that it is an abomination for two men to have sex, I could meet the moment with pensive laments that, yes, some parts of Torah are difficult, but we must try our best to understand. Or, I could say to the text: I love you very much, but this is ridiculous. That the first form is better received does not make it more legitimate. Though it has its place, restricting critique to only the softer form can have the effect of intellectualizing concerns that are felt viscerally, effectively minimizing those concerns in the process.

The appeal of sharp-tongued critiques is about more than just the ability to let loose. It’s about being able to bring one’s whole self to religious conversations. Playing rough with the tradition also communicates a confidence that it is impervious to our barbs. Conversely, tone-policing the expression of Jewish ideas — especially when it comes from a gender that hasn’t been in a position to write centuries worth of commentaries — telegraphs an underserved fragility, one that ensures a generation of “approved” Jewish ideas that are removed from the concerns of actual people.

On the internet, this sharper form of criticism has flourished. Until now, both contributors to and observers of the genre have spent little time theorizing about their own work, but it is time to acknowledge that meme-ified Torah is a genuinely new form of expressing Jewish ideas, one whose reach is already massive and is likely to grow further.

This form of Jewish discourse — one that allows for both caustic and innocent humor, the one that treats absolutely nothing as off-limits — has allowed for a far wider variety of relationships to the tradition, and it allows people to contribute to that tradition even if they do not personally have the wherewithal to write a monograph or give a sermon. It is not marginal; it is the future.