(JTA) — How do we live a life of principle and integrity, without closing ourselves off from others who do not share all of our values?

How do we build bridges and broad tents that include the diversity of human viewpoints and experiences, without forgetting what we stand for?

These are old problems, and evergreen ones.

The Talmud records a crisis from 2,000 years ago, when Rabban Gamliel, the political head of the Jewish community, was deposed as the leader of the main rabbinic academy. His sin? It seems his standards were too high: Rabban Gamliel demanded that all who entered the house of study meet the standard of tokho ke-varo, that their insides should be like their outsides. Like the ark in the Tabernacle, a scholar was meant to be a person of gilded character, inside and out, a paragon of integrity and principle. This was a standard most people cannot meet.

Indeed, on the day Rabban Gamliel was deposed, the barriers to entry were lowered dramatically: We hear of hundreds and hundreds of pews being added until the space was bursting at the seams.

The message of the Talmud, at first read, seems to be this: Lean into love and compassion and be less of a stickler. Sacrifice some integrity and principle; maybe it’s acceptable for the ark to be gilded on the outside without looking too closely at what you will find within. You will be rewarded with a fuller and broader community. And if you stand on ceremony for what you believe, your world will begin to contract.

But that is not in fact the end of the story. At the end of the story, Rabban Gamliel — presumably along with the culture he embodied — returns to head up the study house three weeks out of four. The final picture is one of synthesis, where the communal space is guided by a paragon of principle insisting on high standards, balanced with a breadth of vision that will find a way to let those hundreds of people in.

In the Talmud, this balance requires a rotating cast of characters. For all of us mourning Joe Lieberman, we saw this synthesis, and the utter refutation of the entire dichotomy, in the man we mourn.

Joe Lieberman was tokho ke-varo — his inside was like his outside.

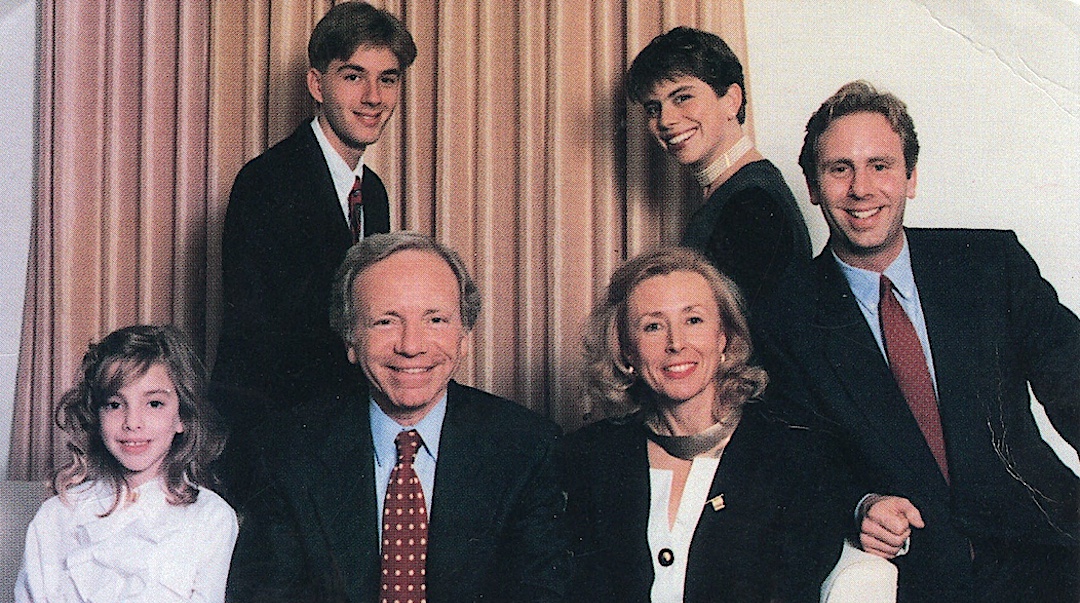

Tokho ke-varo — His inner gilded character and generosity shone through to all those who encountered him. His panim yafot, his gleaming countenance, was not a well-executed politeness. It reflected the inner joy he truly felt when he encountered each person. There was no person, no matter their station, their seniority, their origin, their ideology, who was not capable of evoking this response from him. When he first met me, at age 6 ½, I could tell from the first moment that he loved my mother, but he also loved me, and not just because he loved her. His external kindness reflected internal affection. This was a gift, gratitude for which I can never exhaust, an example I can only hope to emulate.

Tokho ke-varo — His integrity guided his actions. Nothing was done except for principle, sometimes to his political benefit, sometimes not. You knew where he stood, and based on where he stood, you knew how he would respond.

Tokho ke-varo — His inner, private, family life was seamlessly connected to his outward, public-facing life. He was the same person at home and in public. He saw his public service as a reflection of his most deeply held values, the ones he instilled in us. And his interactions with everyone carried the tenderness of a dear friend and a loving parent.

He would have been a star pupil in Rabban Gamliel’s academy

But no one knew more and better how to build bridges and broad tents than he. And he did so through his integrity.

This started at home: As a small child, I saw him leverage his love for and commitment as a father to Matt and Rebecca, the children of his first marriage, to take me on as his child.

He had his home synagogues, beginning with Congregation Agudath Shalom in Stamford, Connecticut; but there was no shul in which he wouldn’t daven.

He saw and found truth in genuinely held political convictions with which he disagreed, because he knew what it felt like to believe in something.

His faith allowed him to connect to others of faith, or to anyone seeking a voice of conviction and principle. He taught me that being an observant Jew should make you more, not less likely, to connect with those of different backgrounds.

His integrity was not a blinding light, but a magnetic field, drawing in fellow travelers and inviting in even adversaries for dialogue and compromise.

There was no limit to the number of benches in his study hall. He could have run the Talmudic academy four weeks out of four — it would have modeled integrity inside and out, and it would have been bursting at the seams, as is this sacred space today.

Oh, how we miss you and need you, Joe. Thank you for reminding us that our deepest convictions can be the most important planks of bridge building. And that the pegs of our integrity are the only things strong enough to anchor the tents of the broad communities our world so desperately needs. We love you.

This essay is adapted from the eulogy the author gave for his stepfather, Sen. Joseph Lieberman, at his funeral. Lieberman died March 25 at age 82.