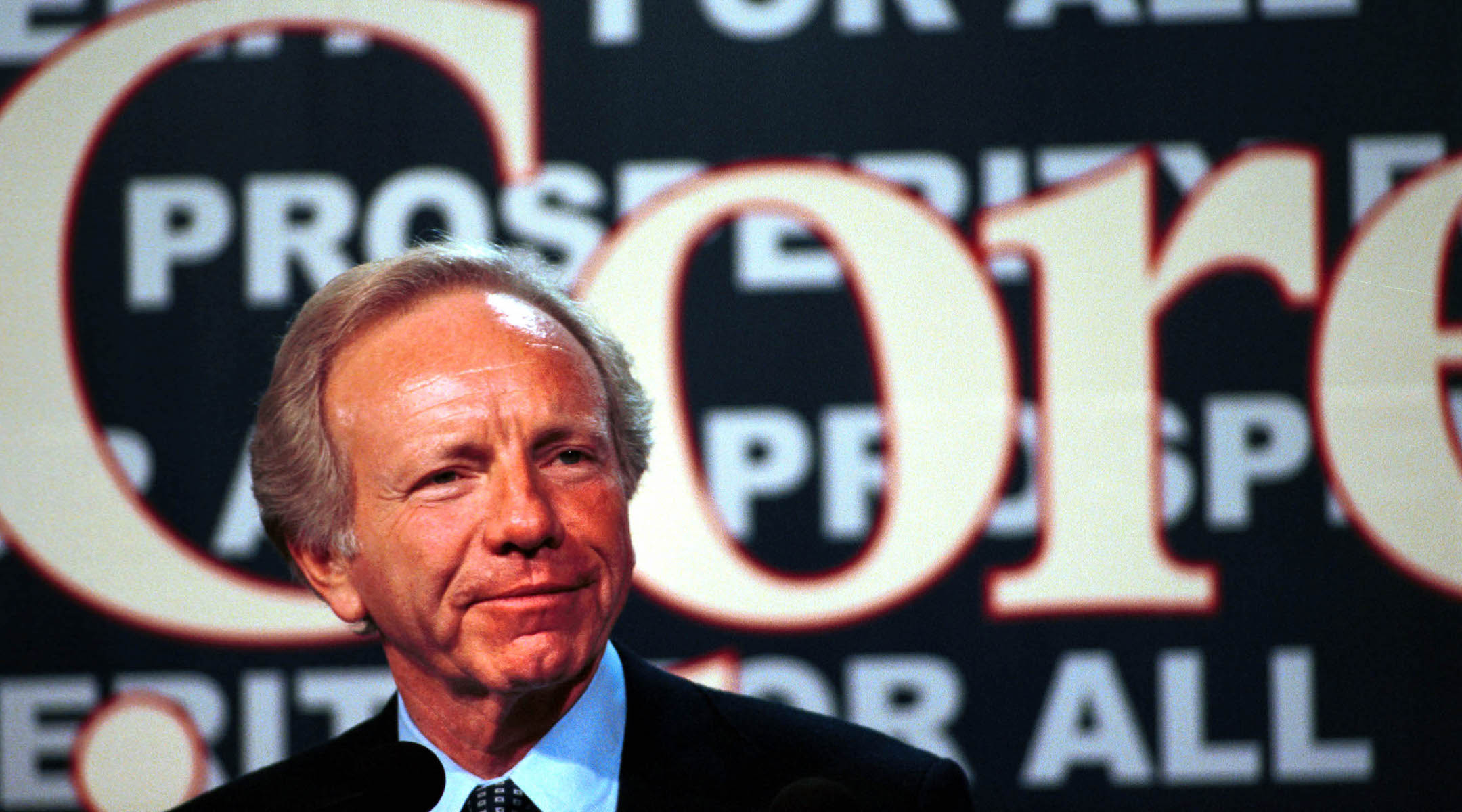

(JTA) – Joseph Lieberman, a longtime senator from Connecticut who as Al Gore’s running mate in 2000 became the first Jewish member of a major presidential ticket, died Wednesday. He was 82.

A statement sent to former staffers and reported widely said Lieberman had suffered complications from a fall.

A moderate — some would say conservative — Democrat turned independent, Lieberman was known for his attempts to build bridges in an increasingly polarized Washington, sometimes losing old friends and allies along the way.

He also became one of the most visible role models for Jewish observance in high places, in contrast to the largely secular Jewish politicians who had preceded him on the public stage. In 2011, he wrote “The Gift of Rest: Rediscovering the Beauty of the Sabbath.” In it he wrote how on Friday nights he would walk the roughly four miles from the Capitol to his home in Georgetown after a late vote so as not to violate Shabbat — to the bemusement and admiration of Capitol police.

In announcing that he would not be running for reelection in 2012, Lieberman spoke in emotional terms about what it meant for the grandson of Jewish immigrants to be considered for a role just a heartbeat from the presidency.

“I can’t help but also think about my four grandparents and the journey they traveled more than a century ago,” he said. “Even they could not have dreamed that their grandson would end up a United States senator and, incidentally, a barrier-breaking candidate for vice president.”

That legacy, the first Jewish candidate on a major ticket, would be the Lieberman legacy to outlast all others, Ira Forman, the former director of the National Jewish Democratic Council, declared at the time.

“It was an electric moment,” Forman recalled of Gore’s choice of Lieberman in 2000. “It galvanized the feeling that everything is open to you.”

The pro-Israel lobby AIPAC memorialized Lieberman as “indefatigable in advancing pro-Israel policy and legislation.” He watched his onetime party drift away from his beloved Israel, and it pained him. Last week, in one of his last public statements, he excoriated Sen. Chuck Schumer, the Jewish senator from New York who called for new elections in Israel.

“Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer last Thursday crossed a political red line that had never before been breached by a leader of his stature and never should be again,” Lieberman wrote in the Wall Street Journal.

Lieberman’s religious orientation also came in to play when he emerged as a voice of traditional values within a party that he feared had surrendered the moral high ground to Republicans.

In 1998, he delivered a floor speech excoriating President Bill Clinton for his affair with an intern, Monica Lewinsky. He called his one-time friend “immoral” and said that Clinton had “weakened” the presidency.

The speech sent out shockwaves — news networks interrupted broadcasts to go to the Senate floor — but it also staved off calls for Clinton’s removal from office. It was credited with salvaging the presidency when the Senate subsequently rejected the U.S. House of Representatives’ impeachment. Through a Democrat’s excoriation of a Democratic president, Lieberman seemed to have punished Clinton enough.

Lieberman’s reputation for outreach to the other side defined his career in the Senate after he arrived in the body in 1989, having been elected after serving as Connecticut’s attorney general. His break with Democratic ranks in backing the first Persian Gulf War in 1991 helped him later in the decade, when he rallied Republicans to support Clinton’s military actions in Kosovo.

Joe Lieberman at a campaign rally in New Hampshire in October 2000. (Darren McCollester/Newsmakers/Getty Images)

In 1992, when Clinton’s campaign was cold-shouldering Arab Americans, the community reached out to Lieberman, despite pronounced differences with him over Israeli-Palestinian issues, because of his reputation for fairness.

James Zogby, the president of the Arab American Institute, once recalled Lieberman’s outrage, and how after one phone call from the senator, Clinton’s headquarters in Little Rock, Arkansas, abashedly opened its offices to Arabs.

Yet it was at his very pinnacle — running for vice president — that signs emerged of how the subsequent decade would play out. He delivered an ineffective — some said even deferential — performance in his debate with Dick Cheney, George W. Bush’s running mate. And during the recount, he undercut one of Gore’s best arguments — questionable absentee ballots from the military — when he told NBC’s “Meet the Press” that they should be honored.

The real turning point came after the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, when the Bush administration launched a political and diplomatic campaign to make the case for war against Iraq.

Like many other Democrats, Lieberman steadfastly backed war. But while many of his Democratic colleagues came to regret their decision, he stuck by it, and even made it the centerpiece of his 2004 campaign for the presidency. He was bitter when Gore, who opposed the war, endorsed Howard Dean for president that year.

Lieberman’s adamant backing of the war led to an insurgency in Connecticut. Liberal Democrats descended on the state to back his anti-war opponent, Ned Lamont, helping him win the primary. It didn’t help that at this late stage, when the Iraq war’s failure had become conventional wisdom, Lieberman wrote an Op-Ed in The Wall Street Journal backing Bush’s strategies.

Establishment Democrats, including a freshman senator from Illinois named Barack Obama, supported Lieberman in the primary but could not see a way to support him once Lamont prevailed. Lieberman ran as an independent, and with the Republican Party refusing to back its candidate, he won with votes from the GOP and independents.

In that election, Jewish Democrats were torn between their loyalty to the party and to Lieberman. Notably, the National Jewish Democratic Council stayed out of the fight.

That loyalty helped Lieberman capture a fourth term and proved he still had ties to the Democratic Party.

But that bridge burned when he made it clear that he’d back his old friend Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), the GOP candidate, in the 2008 election. Lieberman’s announcement led to a tense, whispered conversation with Obama on the Senate floor in which Obama reminded Lieberman of how he had made time to campaign for him against Lamont.

Particularly galling for Democrats was Lieberman’s agreement to endorse McCain on the floor of the Republican National Convention in Minneapolis. McCain even considered Lieberman as a possible running mate.

“He put himself in a position where his longtime supporters, particularly the hard-core Democrats who had supported him over the years, could no longer defend him,” Marvin Lender, who raised money for Lieberman in 2006, recalled in 2011. “I say that recognizing he was a very loyal person to his old friend, but he crossed over a line when he did that and disappointed a ton of people.”

After the election, Obama made it clear that he wanted Lieberman to stay on his side. That meant Lieberman maintained his chairmanship of the Homeland Security committee while caucusing with Democrats.

He still had a bridge or two left to burn: On health care reform — a signature issue for Jewish Democrats — Lieberman equivocated until the last minute, ultimately casting his vote in favor.

His relationship with Obama remained cordial but tense. Lieberman took the lead in criticizing Obama’s approach to Israeli-Palestinian peacemaking as overly confrontational when Obama met last May with Jewish lawmakers.

Lieberman maintained his fierce independence until the end. His career cap was a nod to his more liberal sensibilities, when in the final weeks of 2010 he earned kudos from liberals for enabling repeal in the Senate of the “don’t ask, don’t tell” rule that had made it impossible for gays to serve openly in the military. Gay activists did not fail to notice that Lieberman stuck out the vote, even though it was on Shabbat.

Yet that also was a bridge burner of sorts. When Lieberman a few nights later attended a Republican Jewish Coalition party celebrating the GOP’s win of the U.S. House of Representatives, at least one GOP donor to Lieberman’s 2006 campaign buttonholed him and said he would never again give him money because of his success in leading the “don’t ask” repeal.

Lieberman smiled, said he had to do what he had to do and left the party.

Sen. Joseph Lieberman, left, with Sen. John McCain at the Munich Security Conference in Munich, Germany, Jan. 31, 2014. (Joerg Koch/Getty Images)

“Senator Lieberman is a true mensch and a great American,” the RJC said in a statement at the time. “He showed that it’s possible to have a successful political career while doing what you feel is right — even when what’s right is not what’s in your political best interests.”

Last year he became a founding co-chair of No Labels, an independent group laying the groundwork to put a centrist “unity ticket” on the 2024 presidential ballot. After he wrote a Wall Street Journal op-ed titled “No Labels Won’t Help Trump,” few Democrats were persuaded.

Joseph Isadore Lieberman was born in Stamford, Connecticut, the son of Henry, who ran a liquor store, and Marcia (née Manger). His paternal grandparents emigrated from Poland and his maternal grandparents were from Austria-Hungary. He became the first member of his family to graduate from college when he received a B.A. in both political science and economics from Yale University in 1964. He earned his law degree from Yale Law School in 1967.

Lieberman served for 10 years in the Connecticut Senate beginning in 1970. From 1983 to 1989, he served as Connecticut Attorney General, emphasizing consumer protection and environmental enforcement.

Lieberman was first elected to the United States Senate in 1988, in a major upset over incumbent liberal Republican Lowell Weicker.

Following his retirement from the Senate, Lieberman returned to practicing law, and joined the conservative American Enterprise Institute think tank as co-chairman of their American Internationalism Project. He also held the Lieberman Chair of Public Policy and Public Service at Yeshiva University, where he taught an undergraduate course in political science.

In August 2015, Lieberman became chairman of United Against Nuclear Iran, a group fiercely opposed to efforts by the Obama administration to broker a deal with Iran over its nascent nuclear program.

“While Iran’s leaders may be prepared to make some tactical concessions on their nuclear activities, they would do so hoping that this would buy them the time and space needed to rebuild strength at home — freed from crippling sanctions — while consolidating and expanding the gains they are positioned to make in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Yemen and Afghanistan,” he wrote in an oped in 2013.

Lieberman was married twice. He and his first wife, Betty Haas, were married in 1965 and had two children, Matt and Rebecca; the couple divorced in 1981. In 1983 he married Hadassah Freilich Tucker, who was previously married to Rabbi Gordon Tucker, the former senior rabbi of Temple Israel Center in White Plains, New York. He is survived by his wife and their daughter, Hana Lowenstein; Matt Lieberman and Rebecca Lieberman and a stepson, Rabbi Ethan Tucker.