(JTA) — For two hours, members of Congress questioned three major public school leaders about allegations of student antisemitism — and took them to task for not doing more to counter it.

The three heads of K-12 school systems — in New York City, Berkeley, California and Montgomery County, Maryland, outside Washington, D.C. — all forcefully denounced antisemitism and defended their approach to fighting it.

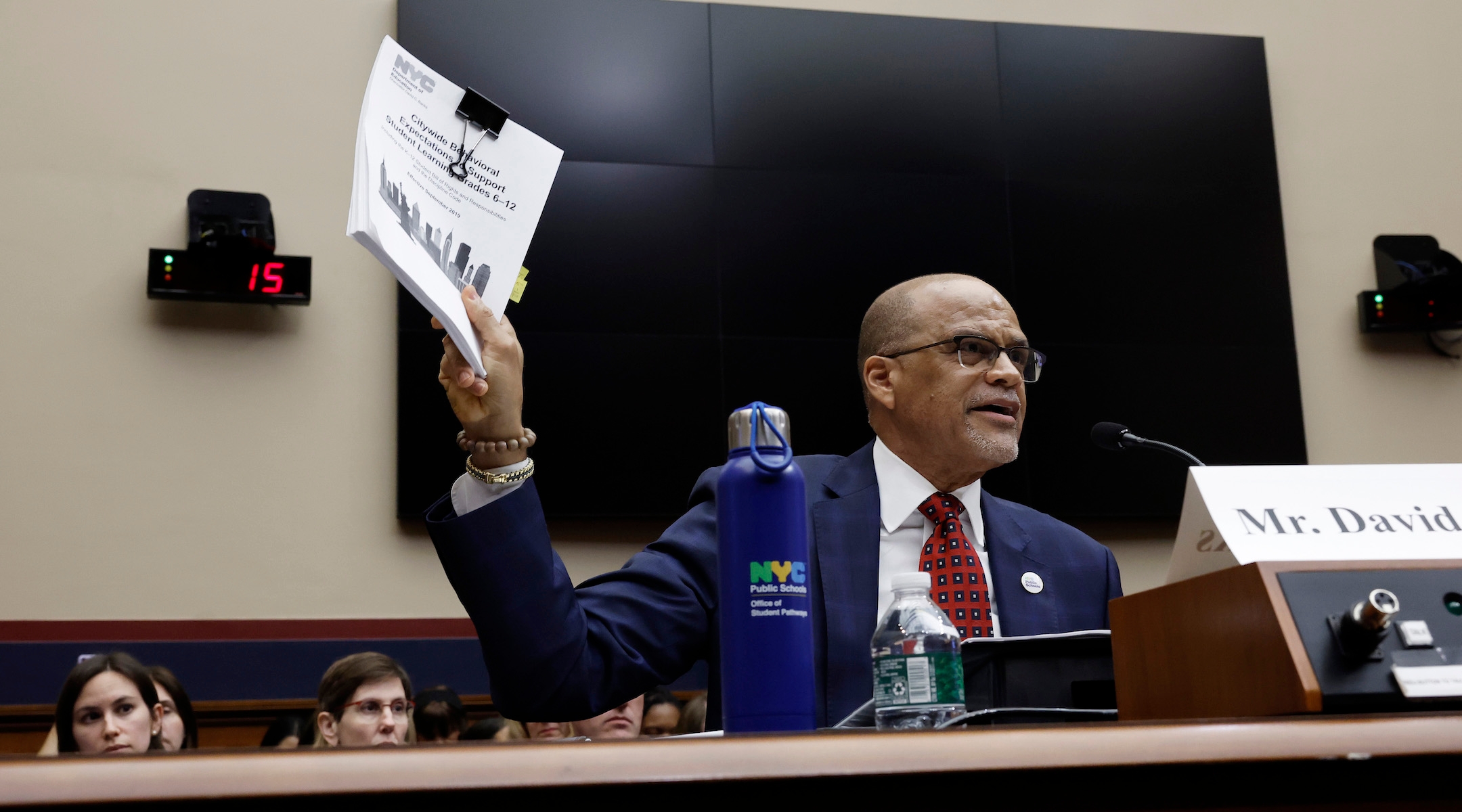

“Our classroom is not insulated from the global stage,” David Banks, chancellor of New York City Public Schools, said in his opening remarks. “There have been unacceptable incidents of antisemitism in our schools. When Jewish students or teachers feel unwelcome or unsafe, that should sound the alarm for us all.”

The hearings were the House Education and Workforce Committee’s first foray into investigating antisemitism at K-12 schools after two bombshell hearings with the presidents of elite universities. Those campus hearings — a third is scheduled for later this month — transformed the national conversation over antisemitism and led to resignations of two Ivy League presidents and widespread college student protests.

Incidents at all three school systems are all currently under investigation by the U.S. Department of Education. And while K-12 schools have not received the same level of scrutiny as college campuses amid the Israel-Hamas war, several school systems — particularly in large cities — have still wrestled with how to deal with various actions by students and teachers that Jewish students and families have found hostile.

Wednesday’s hearing did not approach the marathon length of the university hearings and did not feature the same level of inflammatory or viral exchanges. Still, members of the Republican-led committee pressed the witnesses over whether they had fired teachers and administrators who participated in or failed to stop antisemitism, and questioned how they taught students about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

When the three officials said they had not terminated any staff over antisemitism, the lawmakers painted them as negligent in their commitments to Jewish families.

“So you’ve allowed them to continue to teach hate,” Rep. Aaron Bean (R-Florida), the Early Childhood, Elementary, and Secondary Education subcommittee chair, told Karla Silvestre, president of the Montgomery County Board of Education.

Karla Silvestre, president of the Montgomery County Board of Education, arrives for a hearing with subcommittee members of the House Education and the Workforce Committee in the Rayburn House Office Building in Washington, D.C., May 8, 2024. (Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images)

Silvestre said the district has not fired anybody over antisemitism, though the district has suspended teachers who shared antisemitic content before later reinstating them. Republicans also trained their fire on Banks following allegations of antisemitism at several schools in New York since Oct. 7.

Rep. Brandon Williams, an upstate New York Republican, asked about Banks’ response to a November student riot at Hillcrest High School in Queens that targeted a Jewish teacher. Banks had said Hillcrest’s principal was no longer at the school but was still employed in an administrative role elsewhere in the city’s school system.

“How can Jewish students feel safe at New York City public schools when you can’t even manage to terminate the principal of ‘Open Season on Jews high school’?” WIlliams asked.

“It’s not ‘Open Season on Jews School,’” Banks shot back forcefully. “It’s called Hillcrest High School.” He then cited employee protections.

“Every employee who works in our schools has due process rights, sir,” he said. “We do not have the authority to, just because I disagree, to just terminate someone. That’s not the way it works in our school system.”

One popular form of activism against Israel on the K-12 level has been student walkouts. Asked by upstate New York Republican Rep. Elise Stefanik if his district takes action against students who participate in them, Banks said that policies prevented him from doing so, beyond marking students as absent and cutting class.

Enikia Ford Morthel, superintendent of the Berkeley Unified School District, listens during a hearing with subcommittee members of the House Education and the Workforce Committee in the Rayburn House Office Building, Washington, D.C., May 8, 2024. (Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images)

In at least one case, the hearings resurfaced a long-running controversy over antisemitism in public school curriculums. Enikia Ford Morthel, superintendent of Berkeley Unified School District, faced tough questions over lesson plans about Israel and Oct. 7 in the district.

The plans were formulated after students said they wanted to learn more about the attacks, Morthel said. But one of the groups involved in designing the lessons was the Liberated Ethnic Studies Consortium, which promotes an early draft of the state’s ethnic studies curriculum that Jewish groups decried as antisemitic.

“You specifically chose to work with a group whose work product was rejected by political leaders throughout California as antisemitic,” said Rep. Kevin Kiley, a California Republican. He also objected to district materials that included a positive view of the slogan “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free,” which pro-Palestinian activists view as a call for liberation but which many Jews see as advocating Israel’s destruction. At least one school district, in Minnesota, is being investigated for suspending students who chanted the phrase.

Morthel responded that the Liberated Ethnic Studies Consortium was a “thought partner” and “resource” on Berkeley’s lesson plans, but was not the sole author of the curriculum. She also defended the lesson’s incorporation of the Palestinian perspective on “From the river to the sea.”

“We definitely think it’s important to expose our students to a diversity of ideas and perspectives,” she said. Earlier, she and the other witnesses had said they understood Jews viewed the phrase as antisemitic.

Some Democrats on the committee sought to defend educators, with New York City Rep. Jamaal Bowman — a progressive and former teacher who is a harsh critic of Israel — insisting that antisemitism was not a pervasive problem in public schools.

“Our teachers in our schools are not teaching hate, the majority of them,” he said. “Teachers make mistakes, and teachers need to be educated and disciplined when necessary when they do make those mistakes.”

The day before the hearing, the U.S. Department of Education announced it was opening a Title VI “shared ancestry” discrimination investigation into the Berkeley district, based on an antisemitism complaint filed by the Anti-Defamation League and the pro-Israel legal activist group Brandeis Center for Human Rights Under Law. Morthel said that the district was aware of the investigation and planned to fully cooperate. The ADL’s involvement in the case is notable, as the organization has otherwise barely touched the rash of more than 100 other post-Oct. 7 Title VI investigations. (Both New York and Montgomery County also have active Title VI antisemitism investigations opened against them; New York’s relates to a former teacher, who no longer works for the school, who accused Israel of genocide and ethnic cleansing.)

In the room during the hearing were a handful of Jewish students and parents from the districts under the microscope. At least one of those students told JTA she was disappointed that lawmakers didn’t push harder on discipline for antisemitism.

“I thought I was going to get a sense of justice from this. And that wasn’t the case,” Darci Rochkind, a high school senior in the Montgomery County district and president of her school’s Jewish student union, said. She wanted lawmakers to press Silvestre more on reappointing teachers who were suspended for suggesting that elements of the Oct. 7 attacks were fabricated.

Rochkind, who has a fellowship with the Jewish National Fund and is attending Dartmouth College in the fall, said she was still “really grateful the committee hosted it because I think it shines a light with what’s going on within K-12 schools.”

But, she added, “there was definitely a feeling of frustration.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story misidentified Rep. Kevin Kiley. This has been corrected.