(JTA) — The dark red wall that welcomes visitors at the Museum of Jewish Heritage’s new exhibit, about the rescue of Danish Jews during the Holocaust, offers an introduction that’s both typical and anything but.

As in the beginnings of most exhibits, the wall offers background about the dramatic story visitors are about to learn — but it also includes a “content warning” that’s clearly written for children.

“If you feel scared or sad, you can take a break. Try taking a few deep breaths or talking with an adult,” it reads.

The warning is the first sign that the exhibit at the museum in Lower Manhattan sits at the front lines of a shifting debate among educators about the right age for children to learn about the Holocaust.

“Courage to Act: Rescue in Denmark,” which opened last fall, tells one of the few hopeful, uplifting stories that can be told in the context of the Holocaust: the narrative of how the citizens of Denmark banded together to save more than 95% of the country’s Jewish population from the Nazis. It includes illustrations by a children’s book artist; videos of actors portraying real Danes from the time; and a replica of a large boat that ferried some Danish Jews to safety in Sweden.

What the exhibit is not full of is photos that depict the pain and suffering of the Holocaust.

The project is the museum’s first exhibit designed to appeal to guests as young as 9 — ages “9-99,” in the words of its head curator Ellen Bari — and represents the most radical revisioning yet of new frontiers in Holocaust education.

“I do think it’s a new way to approach history,” Bari told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Museums and educators are wrestling with the question of how to reach younger audiences further and further removed from the horrors of the Holocaust — and from the fading number of survivors whose firsthand testimony has anchored many a Holocaust curriculum since the discipline was established. Experts in the field say finding new and innovative ways to introduce young people to the topic early has become a crucial part of their job.

“For us, thinking of Holocaust education really as a lifelong learning process, this can’t just be something that you read Anne Frank or Elie Wiesel’s ‘Night’ in upper middle school and high school, and that is your exposure to the topic,” Jenna Leventhal, interim director of programs at the USC Shoah Foundation, told JTA. “We need to start younger.”

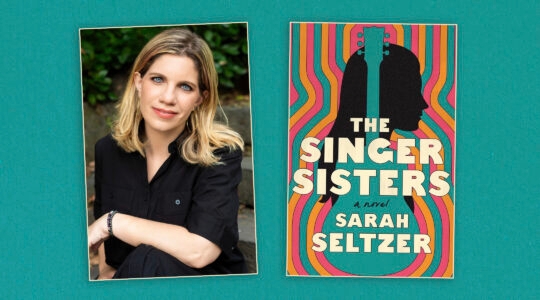

An illustration of one of the exhibit’s featured characters that help tell the story. (Illustration by Sveta Dorosheva/Courtesy of The Museum of Jewish Heritage – A Living Memorial to the Holocaust)

That question takes on special urgency in light of the Hamas attacks on Israel on Oct. 7 that resulted in the largest number of Jews killed in a single day since the Holocaust, and the increasing number of voices worldwide accusing Israel of perpetrating genocide in the Gaza Strip in retaliation. The museum’s board chair, Bruce Ratner, said Oct. 7 had created a new context for the exhibit.

“As a museum about the Holocaust and Jewish heritage, we believe it is always important to revisit the history of antisemitism and the Holocaust. At a time when Israel has been attacked, it is even more important,” Ratner said in a statement. “This exhibition is about people coming together in times of war and terror. It is critically important to remember that there are instances, even during the Holocaust, where people of good will make an effort to help.”

Holocaust educators everywhere are trying new and different ways to reach children. The Illinois Holocaust Museum in Skokie, in partnership with the USC Shoah Foundation, has launched a series of immersive virtual reality films about the Holocaust designed for middle schoolers and up, along with an “Ask a Survivor” artificial-intelligence project that has been endorsed by Jewish Second Gentleman Doug Emhoff. The museum is currently engaged in discussions with state education agencies to bring the VR project directly to public schools.

In addition, “White Bird: A Wonder Story,” an upcoming dramatic film starring Helen Mirren and Gillian Anderson, aims to tell the story of the Holocaust from a family-friendly perspective. (Previously scheduled to open last summer, it was postponed until October 2024 due to the actors’ strike.) A National Geographic dramatic miniseries about the family that hid Anne Frank’s family, “A Small Light,” was released last summer and also sought a general audience. And The Light in the Darkness, a recent, independently produced video game about the experiences of French Jews under Nazi occupation, aims to reach young audiences — as did its creator’s launch of a virtual Holocaust museum inside the popular video game Fortnite.

The USC Shoah Foundation is actively working with the Anti-Defamation League’s Holocaust education arm, Echoes & Reflections, to improve classroom materials for young people. It is also undertaking a study to measure the long-term effects of increased exposure to Holocaust education at a young age, Leventhal said.

Another illustration shows the Gerda III boat, one of the many used to ferry Jews to safety from Denmark to Sweden. The exhibit features a full-size replica of the boat. (Courtesy of The Museum of Jewish Heritage – A Living Memorial to the Holocaust)

But catering lessons about antisemitism and genocide to children, even (or especially) when kids their own age were among the victims, is no easy task. Caught up in the current rise in book bans at public schools are books on the Holocaust — even those written with young readers in mind — that some parents claim are age-inappropriate. Some Holocaust museums refuse to try, believing that the history is simply too traumatic for young children to bear.

“I usually say that if a child is too young to hear about mass murder (which is the story of the Holocaust) then they are too young to begin their study of this history,” Shelly Cline, director of education at the Midwest Center for Holocaust Education in Kansas City, told JTA in an email.

Cline’s museum won’t introduce the concept until seventh grade: “We find that any younger and they aren’t able to intellectually engage with this material, which is an essential piece.”

The Museum of Jewish Heritage has attempted to address this challenge by enlisting children as consultants on its exhibit. Curators invited a range of classrooms, including local public schools, Jewish schools and a Quaker school for children with learning disabilities, to provide feedback on the wording and presentation of the exhibit. The museum then made changes based on input from the children on material that would be too confusing or disturbing for younger audiences. They also hired child actors to portray the exhibit’s central characters in video vignettes whose scripts were also vetted by children.

“Sometimes we thought that the images might be too much for a younger audience, or even some people who were older, because some of them did show some pretty heavy stuff,” said Izzy Miller, 12, an eighth-grader at Mary McDowell Friends School in Brooklyn who consulted on the exhibit.

Like the three other students from her school who spoke to JTA about their work on the exhibit, Miller is not Jewish (although one other student had a Jewish grandfather). But the kids’ feedback — which included comments to better explain descriptions of Jewish customs that non-Jewish children might not understand, and suggestions to tone down some of the graphic imagery — made its way into the final exhibit. The students said they particularly flagged images of “Nazi brutality” and starving children.

The exhibit also includes live-action videos. (Courtesy of The Museum of Jewish Heritage — A Living Memorial to the Holocaust)

The Museum of Jewish Heritage formed a crucial part of New York City’s plan for combating rising antisemitism among youth in 2020, with the city mandating field trips for eighth- and 10th-graders who live in heavily Orthodox neighborhoods of Brooklyn.

One key difference in the museum’s approach for this age group: reframing the main idea less as an earth-shattering historical atrocity than as a lesson about fairness. This allows instructors to play off of students’ natural inclinations to identify unfairness in their own lives, the quality that makes them ideal students for Holocaust education, Bari said.

“In the past, middle school kids visiting the museum have been morally outraged by the injustice and unfairness of it all,” Bari said. In fact, she added, middle schoolers can be less cynical and more receptive to lessons from the Holocaust than high school students, who are the main focus of most statewide Holocaust education mandates.

With this in mind, the exhibit’s curators said it was important to lean into positivity — a trait that tends to be in short supply in Holocaust lessons. “For younger visitors especially, we wanted to leave them with a sense of hope,” Elizabeth Edelstein, the museum’s vice president of education, told JTA. “Because we’re looking to reach 9 to 12 year olds, for whom the idea of what’s ‘fair’ and ‘unfair’ are particularly interesting in their own development.”

For years, Holocaust education courses centered around one tried-and-true narrative: the litany of horrors the Nazis perpetrated on the Jews. The piles of confiscated shoes, so ubiquitous in Holocaust museums they became a punchline on “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” were unambiguous visual representations of the inhumanity of the death camps.

Leventhal calls this method, which was popular in the 1970s and ’80s, “the shock-and-awe approach.” Looking back, she says, “That wasn’t particularly effective in terms of learning outcomes. It just makes students scared.”

Edelstein agrees. “Twenty years ago, the material about the Holocaust might read like a narrative about the actions that the Nazi Party took,” she said. “‘The Nazis did this in this year, then they did this, then they said this, then they did this.’ Well, what’s missing is the entire experience of those to whom they did things.”

Luke Berryman, a Chicago-based Holocaust educator, also suggests a focus on the Nazis’ targets — especially on those who resisted. “We must do more to cast spotlights on Jewish resistance to the Holocaust and on the internal chaos that characterized Nazism,” he wrote in Education Week. “Students are frequently taught to see Jews as ‘lambs’ who went to the gas chambers without question and Nazis as cold but efficient supermen.”

Kelley Szany, senior vice president of education and exhibitions at the Illinois Holocaust Museum in Skokie, also sees negative long-term effects of showing “piles upon piles upon piles of bodies or images of Jews” to students. Hers is a variation on the writer Dara Horn’s argument, in a widely discussed Atlantic article, that too much Holocaust education focuses on the murder of Jews, and not on the diverse, rich lives they led before the war, and revived after.

“While there is a place for that, what you’re doing is continuing to victimize the Jewish people over and over and over again, and showing that they are people who have no agency, who have no dignity,” she said. “No one likes to be shocked and horrified. And that shouldn’t be your goal with Holocaust education. Your goal should be to educate; your goal should be to enlighten.”

For the kids who got an early look at the museum, this goal appeared to pay off. Even the students who had entered their consulting roles without much knowledge of the Holocaust came to understand the scope of it through their work.

“When I hear about stuff like the Holocaust, it’s like, wow, humanity has actually done something like this,” said Sam Worthy, 14. “And it does make me more aware of a lot of the possibilities that can happen within this world.”