(JTA) — One of the most prestigious prizes in Jewish book publishing has gone to a nonfiction book that, by suggesting how Arabs and Jews might have learned to live together in historic Palestine, offers a glimmer of hope for a better future.

That’s one way to read “Palestine 1936: The Great Revolt and the Roots of the Middle East Conflict,” by the American-Israeli author Oren Kessler. There other way is to see the events described in the book — a period of military and political consolidation by Zionists and near total rejection of a Jewish state by the Palestinians — as the inevitable harbinger of the bloody impasse of the next 88 years.

In its announcement earlier this month, The Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature said its top prize, $100,000, was going to Kessler’s book for “its nuanced and balanced narrative on the origins of the Middle East conflict with far-reaching implications for our time.” The annual prize is administered in association with the National Library of Israel.

The book focuses on the period between 1936 and 1939, when Arabs living under the British Mandate rose up against a swelling Jewish population and the Brits in charge. Kessler, who has worked for various think tanks as well as the Jerusalem Post, cites estimates that 500 Jews, 250 British servicemen and at least 5,000 Arabs died in the rioting and the ensuing British crackdown.

In the wake of the violence, Britain’s “Peel Commission” proposed partitioning the mandate into Jewish and Arab states — while placing limits on Jewish immigration. The Zionist establishment, led by David Ben-Gurion and Chaim Weizmann, accepted the proposal; Mohammed Amin al-Husseini, the grand mufti of Jerusalem and the de facto leader of the Palestinian Arab community, rejected the idea and called for jihad.

Kessler calls the events “a story of two nationalisms, and of the first major explosion between them.” The Jews would turn the rebellion to their advantage, by professionalizing their military (with Britain’s help), expanding agriculture and industry and moving into the next tumultuous, tragic decade with the confidence that they could withstand Arab resistance.

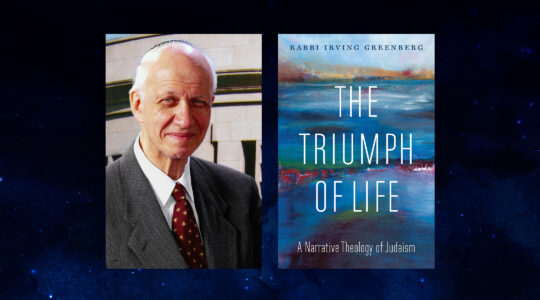

Oren Kessler, author “Palestine 1936.” (Hadas Parush; Rowman & Littlefield)

The Palestinians, meanwhile, emerged from the revolt weakened politically, economically and militarily. Historians on both sides agree that the failure of the revolt set the stage for what the Palestinians call the Nakba — or “catastrophe” — and Israel’s triumph in its 1948 war for independence.

Although a work of history, the book landed on the eve of Oct. 7, and inevitably offers fuel for the debates central to the protests and counter protests that followed the Hamas attack on Israel and the Israelis’ subsequent war in Gaza: Are the Palestinian Arabs victims of a “settler colonial project,” or their own failed leadership? Can two people so at odds share the land, either by dividing it or creating some sort of confederation? And might knowing this history bring both sides closer to a resolution?

“This is the more optimistic version of the answer,” Kessler told me last week, when I put the last question to him. “I think my book and this chapter in history is full of ‘what if’ questions. The idea that things could have indeed gone differently and that we weren’t fated for endless conflict suggests maybe they still can go differently in the present and the future.”

What if, he asks, Herbert Samuel, the British high commissioner for Palestine, had appointed a moderate instead of al-Husseini as grand mufti? What if the two-state solution offered by the Peel Commission report in 1937 had gone through?

“Jews would have gotten less than 20% of the country and there would have been no Palestinian refugee crisis. There would have been no Nakhba in 1948. The Gaza Strip would not be teeming with refugees today,” Kessler said, describing what he knows are unknowable but still strong possibilities.

As a counter to the mufti, who would later line up with Adolf Hitler and further discredit the Palestinian cause, Kessler offers an extensive treatment of Musa Alami, a Palestinian nationalist known for his relationships with the British and the Jews. Alami met several times with Ben-Gurion during the 1930s, suggesting ways in which Jewish national ambitions might coexist within a regional majority of Arabs, with both sides gaining from the economic and public health progress being made by the Jews.

“Despite diametrically opposed political aspirations they met in an atmosphere of real candor and respect, and they really tried to reach a modus vivendi, to reach some kind of agreement that both sides could live with,” Kessler explained. “Alami was not a peacenik. He does his part for the Arab Revolt, and then some. He’s not opposed to violence, nor is Ben-Gurion.

“But I do think his personality was kind of the polar opposite of the mufti’s in his ability to hear the other side, to understand the other side and to try to reach a solution. And it gives a glimpse I think of perhaps what could have been had things gone a bit different.”

A pessimist, Kessler conceded, would reject this hopeful vision out of hand. In the book, as in our interview, Kessler strives to view the emerging Jewish state from the Palestinian perspective. “It’s not that difficult to understand that people who were living in a certain land and whose ancestors have lived there for centuries wouldn’t look all that kindly on another people coming in en masse,” said Kessler. “We don’t need a very active imagination to understand that.”

But the question, he continued, “is how they responded, how they registered their opposition. And with every rejection by the Arabs in Palestine, their position got worse and worse and it continues to this day.”

Kessler mostly leaves it to readers to decide if the lessons of the 1930s are useful in 2024. He’d also like his book to be seen as a lens on a time period that hasn’t gotten its due, at least in English, and one that has “so many fascinating, complex and compelling characters on all three sides of the Palestine triangle: the Jews, the Arabs and the British.”

They include household names such as Winston Churchill and Ben-Gurion, and more obscure figures like Orde Wingate, the Bible-thumping British military strategist who helped build up the Jewish army and liked to greet visitors in the nude.

But at the end of the book he returns to Musa Alami, who lived most of the rest of his long life (he died in 1984) exiled from his native Jerusalem, raising money and international support for Arab refugee youths living in Jordan.

In an interview after the Six-Day War, Alami offered both sides a prescient warning that sounds what Kessler calls “a note of hope”: “You are not considering the future — you are only considering the present,” he told the Israelis. “And we are not considering the distant future — only our present suffering. But I do believe, still now, that this country has the makings of peace.”